Before the Revolution:

Science, Pictures & Baroque Maps

In the years before independence, colonists supported the ideals of the Enlightenment, including the project of mapping the world. As a result of new scientific and commercial surveys, a different generation of maps entered the American marketplace. Starting around 1750, two kinds of overview maps were most popular: those showing European imperial possessions and sectional close-up plans of local places. Both types looked decidedly modern. Place names, topographic symbols, and grid lines all but erased the century-old tradition of using exaggerated and stereotyped pictures of wild beasts, human figures, or city views for distinguishing places or peoples. The leaner, more scientific look allowed mapmakers to distance themselves from accusations of misrepresentation and mythmaking. Yet, pictures were not banished completely; they were simply relegated to the map margins. Elaborately engraved cartouches reveal features that resonate with decorative designs popular during the Baroque period of the 1700s.

So Geographers in Afric maps,

with Savage-Pictures fill their Gaps;

And o’er uninhabitable Downs

Place Elephants for want of Towns

Jonathan Swift, On Poetry, A Rhapsody (1733)

Published in 1733, Jonathan Swift’s poem (above) satirizes the look of eighteenth-century maps. Swift mocks mapmakers for letting maps cover up geographical ignorance, using pictures of native peoples or animals instead of drawing the topography appropriate to the region or admitting their lack of knowledge by leaving parts of the map blank. Swift’s quote is also intended to mock Englishmen, and thus also American colonists, for expecting map pictures to reflect a geographical bias. While most of the imagery is offensive to us today, it was common practice throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Western mapmakers always used ethnic stereotypes when representing non-European countries or continents.

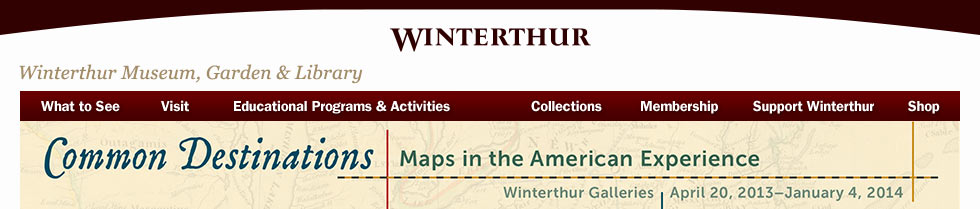

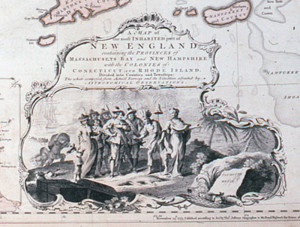

A Map of the Most Inhabited Part of New England

Probably drawn by Braddock Mead

Published by Thomas Jefferys

London, England; 1774

Etching and engraving with watercolor on wove paper

1974.169 Museum purchase

The Jefferys and Mead map of New England seen here demonstrates how craft and taste transformed maps into a scientific tool and ornamental picture. The map is compiled from a variety of sources, most of which are—true to professional etiquette—identified on the map itself (center right). The abstract technical look, however, contrasts with the ornamental cartouche (lower right), which shows one of the scenes defining American history: the Pilgrims making landfall at Cape Cod in 1620. By populating the cartouche with a theatrical cast of characters consisting of English men and women, a Native American, and the figure of Liberty, the map balances its new factual look with eighteenth-century iconographies imagining the history of contact and conquest.

I hav[e] often seen your Maps hung up in Houses, not because they were reckoned useful, but ornamental.

Letter to the public by “Geographus,” Virginia Gazette (January 31, 1771)

Carte des Possessions Angloises & Françoises du Continent de L’Amérique Septentrionale

Drawn by Jean Palairet

Engraved by Thomas Kitchin

London, England; 1755

Etching and engraving with watercolor on laid paper

1980.36 Museum purchase

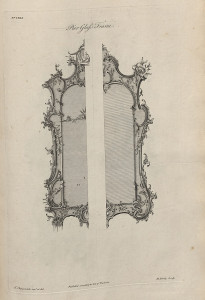

Cartouches provide instructive object lessons for adaptive illustration. When Thomas Kitchin used a fluted and floral design for his cartouche of the Carte des Possessions, he was imitating decorative patterns published in influential architectural handbooks such as Thomas Chippendale’s Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director. The design of cartouche frames tended to be modeled on picture and mirror frames; human figures were often borrowed from popular fashion plates. For example, the figures of the Puritans in the Jefferys and Mead cartouche strongly resemble ethnographic sketches of international costumes. Based on pattern books and stock figures, pre-Revolutionary cartouches provided allegorical depictions of colonial life that told two stories: organic forms indicated the fertility of the land, and social scenes predicted a peaceful economic future in North America.

The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director

Thomas Chippendale

London, England: J. Haberkorn, 1754

NK2542 C54 1754 F Printed Book Periodical Collection, Winterthur Library

Frame

England; 1740‒70

Gilding and gesso over wood

1970.1428b Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont

“Habit of a Flemish Gentleman in 1620” from A Collection of the Dresses of Different Nations, Antient and Modern, Particularly Old English Dresses

(exhibited as photographic reproduction)

London, England: Thomas Jefferys, 1757‒72 (Vol. 2, p. 62)

Harry Elkins Widener Collection, Harvard University Library

A Map of the Most Inhabited Part of New England (detail)

Probably drawn by Braddock Mead

Published by Thomas Jefferys

London, England; 1774

Etching and engraving with watercolor on wove paper

1974.169 Museum purchase

During the French and Indian War, colonial interest in geography resulted in the first increase in American map production and consumption. Newspaper ads offered maps along with luxury items (“silver snuff boxes” and “fine crystal”) and everyday necessities (“linen sheeting” and “fishing tackle”). Philadelphia mapmaker John Evans mastered the art of merchandizing by offering his maps on different materials (paper, calico, and silk) and in different formats (wall map, pocket map, and book insert). Between 1750 and 1775, colonial newspapers advertised maps mostly along with goods associated with literacy and refinement.

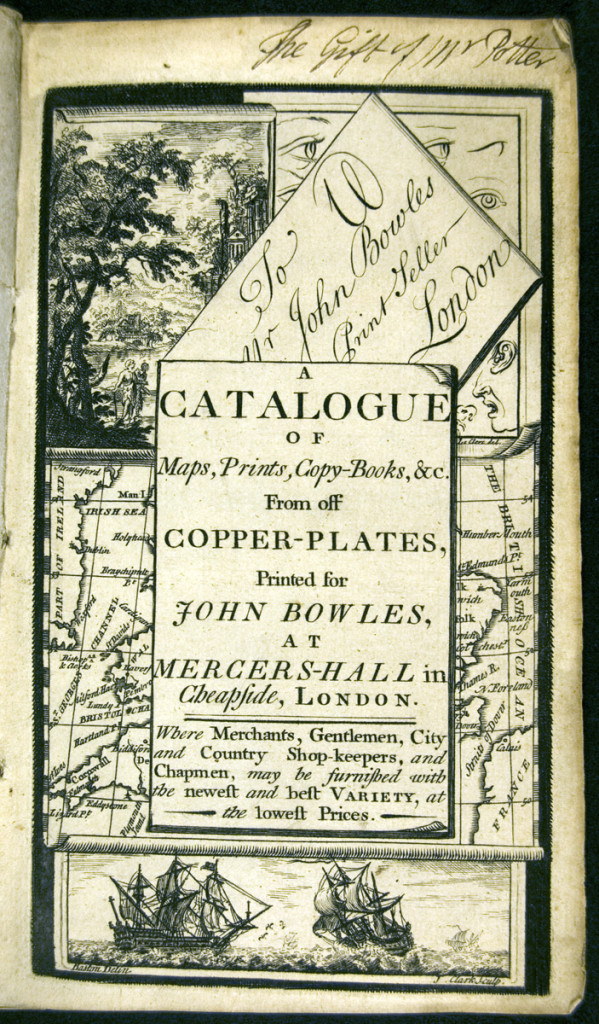

A Catalogue of Maps, Prints, Copy-books &c. from Off Copper-plates

(exhibited as photographic reproduction)

John Bowles

London, England: Mercers-Hall, 1731

University of Delaware Special Collections

Map catalogs were a unique product of the 1700s. Listing old and new maps indiscriminately, sellers responded to a growing desire among middle-class patrons for information about territorial conflicts as well as catastrophic events, such as the 1755 earthquake in Lisbon, Portugal. As the catalog title and frontispiece by John Bowles show, print sellers perpetuated the notion that maps were at once ornamental picture and scientific drawing. Purchased along with decorative prints showing landscapes and seascapes for a price starting at 5 shillings (or $60 today), large maps quickly emerged as a status symbol for the new American middle class.

Advertisement

Advertisement

(exhibited as photographic reproduction)

The Pennsylvania Gazette

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; November 27, 1755

NewsBank

Early American newspapers grant rare insights into the economy of mapmaking. Throughout the 1700s, most maps were the product of individual makers and entrepreneurs who relied on subsidies in the form of small business grants and subscription lists. Once a map was made, however, it was up to the cartographer to generate sales. Lewis Evans perfected the art of selling by packaging his maps in multiple formats, including offering a pamphlet on American geography as a bonus.

Geographical, Historical, Political, Philosophical, and Mechanical Essays

Lewis Evans

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Benjamin Franklin and David Hall, 1755

E199 E92g Printed Book and Periodical Collection, Winterthur Library

Accounts of American geography written by Americans were rare before the Revolution, but surveyor and mapmaker Lewis Evans was an exception. He greatly influenced geographic knowledge about the Mid-Atlantic colonies by describing and analyzing his maps. In order to encourage the sale of his essays, Evans tipped his celebrated General Map of the Middle British Colonies into the pamphlet.

A General Map of the Middle British Colonies in North America

Drawn by Lewis Evans

Engraved by James Turner

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; 1755

Silk

Collection of Barry MacLean

Printed on raw silk, this copy of A General Map of the Middle British Colonies by Lewis Evans is exceptionally rare. It was compiled from original surveys, local maps, and travel reports and fulfilled two important functions. With great accuracy, it delineated Indian lands, which were being contested by colonial proprietors. More significantly, it documented a political view held by many intent on protecting and developing the American colonies. Arguing for the British-American consolidation of the Ohio territory, Evans incurred the ire of the press and, accused of libel, spent time in prison shortly before his untimely death in 1756. While the map shows Evans to be a meticulous cartographer, its inscriptions reveal an astute scientific observer of geology, geomorphology, astronomy, and meteorology.

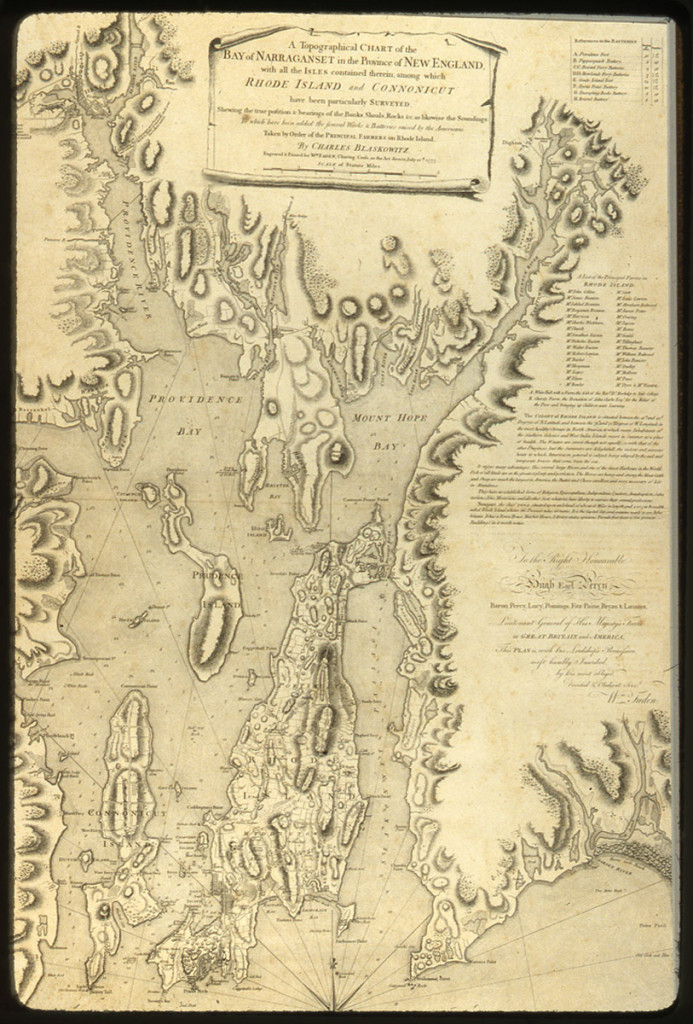

A Topographical Chart of the Bay of Narraganset in the Province of New England

Drawn by Charles Blaskowitz

Engraved and published by William Faden

London, England; 1777

Etching with burin work on laid paper

1960.322 Museum purchase

With the outbreak of the American Revolution, colonial and British mapmakers increased the output of topographical maps that showed the relief of small and often strategic areas such as bays, harbors, and towns. The Blaskowitz map was the most important one of the area around Providence and Newport, Rhode Island. Prepared for British officers, it pitted positive descriptions of New World fecundity (“The horses are boney and strong, the Meat Cattle and Sheep are much the largest in America, the Butter and Cheese excellent”) against negative commentaries dismissive of colonial culture (“It has a Town House, Market House, Library and a spacious Parade, but there is few private Buildings in it worth notice”). Using the word chart and the inclusion of hydrographic information, the map appealed to land and naval officers as well as civilian parties following the events of the war.

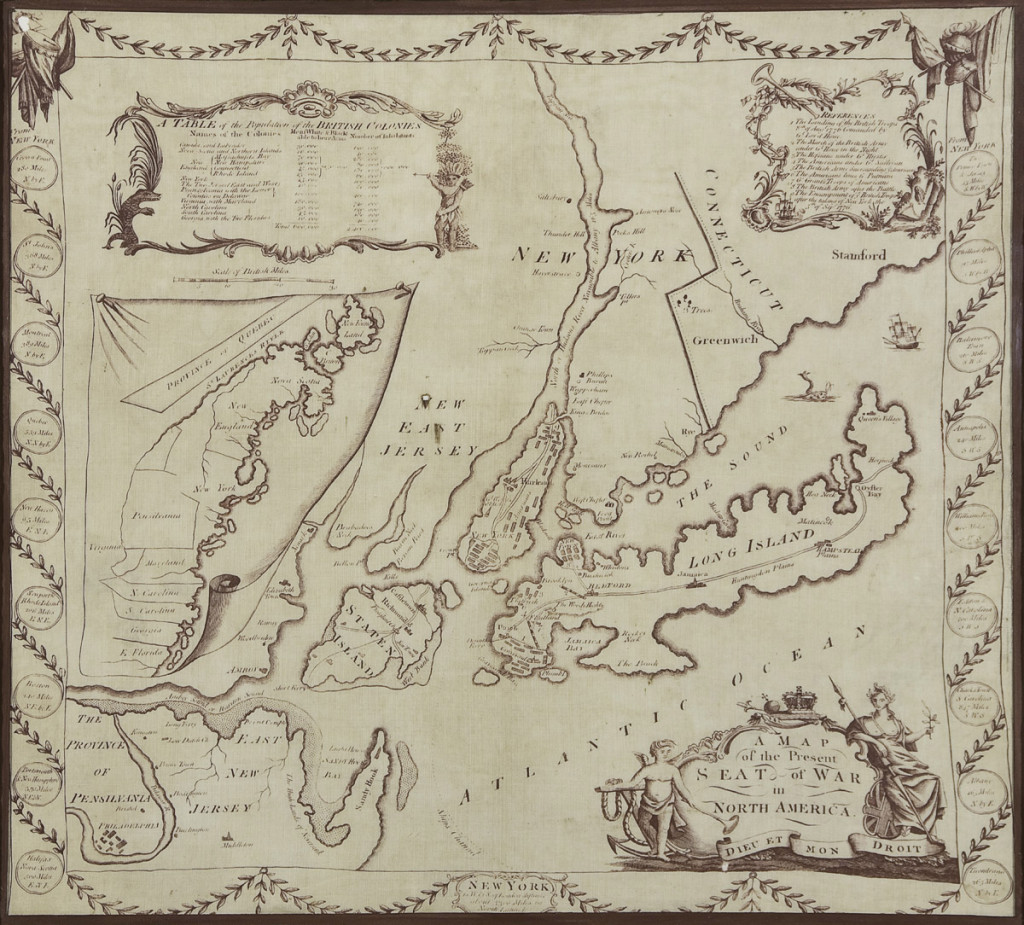

A Map of the Present Seat of War in North America (Handkerchief)

Probably England; 1776–89

Engraving on cotton or linen

1959.965 Gift of Henry Francis du Pont

Throughout the 1700s, map handkerchiefs were fashionable objects popular during times of national crisis. They were intended to celebrate military victories by showing specific battle sites. The handkerchief on display commemorates the Revolutionary War from a British perspective. A number-sequenced legend (upper right corner) gives a blow-by-blow account of General Howe’s campaign against the colonists, culminating in the capture of New York City in September 1776. Worn as a necktie or pocket cloth, this map handkerchief advertised the owner’s loyalist sentiment.