Maps and Masses:

Cartography in the Industrial Age

Westward expansion, immigration, and military conflicts made the study of maps a priority in the lives of men, women, and children during the antebellum decades and beyond. Major surveying projects and advances in printing technology—such as the invention of lithography and the steam-powered rotary press—turned maps into an industrial product. Mass production ensured universal access, and maps were transformed into a flexible consumer good. They addressed diverse needs. School and thematic maps showing gold fields and election campaigns competed with miniature guides and gigantic overviews. Long before the Civil War, wall maps had become permanent fixtures in schoolrooms. They even entered window displays in America’s first shopping districts and were feted at commercial fairs, including the 1853 Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations in New York City’s Crystal Palace.

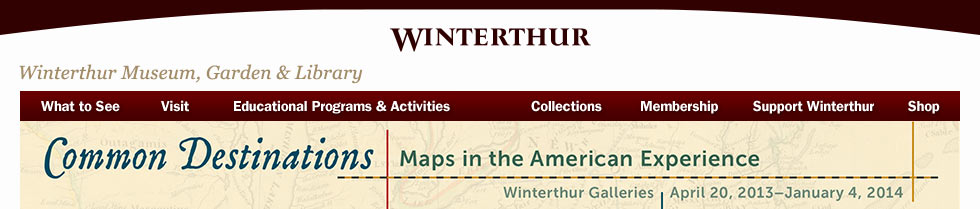

Pictorial Map of the United States

Published by Ensign & Thayer

New York, New York; 1849

Hand-colored lithograph

Collection of Barry MacLean

Publishers like Horace Thayer & Company sold wall maps in the tens of thousands. Their Pictorial Map was popular for patriotic and pedagogic reasons. Scenes showing historical events and battles frame the nation’s territory from coast to coast. Two large iconographic inserts commemorate contributions made by the American military and farmers. In this early stage, the map calls San Francisco “Yerba Buena,” but the colorist did anticipate the California Gold Rush. Since the early 1800s, states and regions have been distinguished by specific colors.

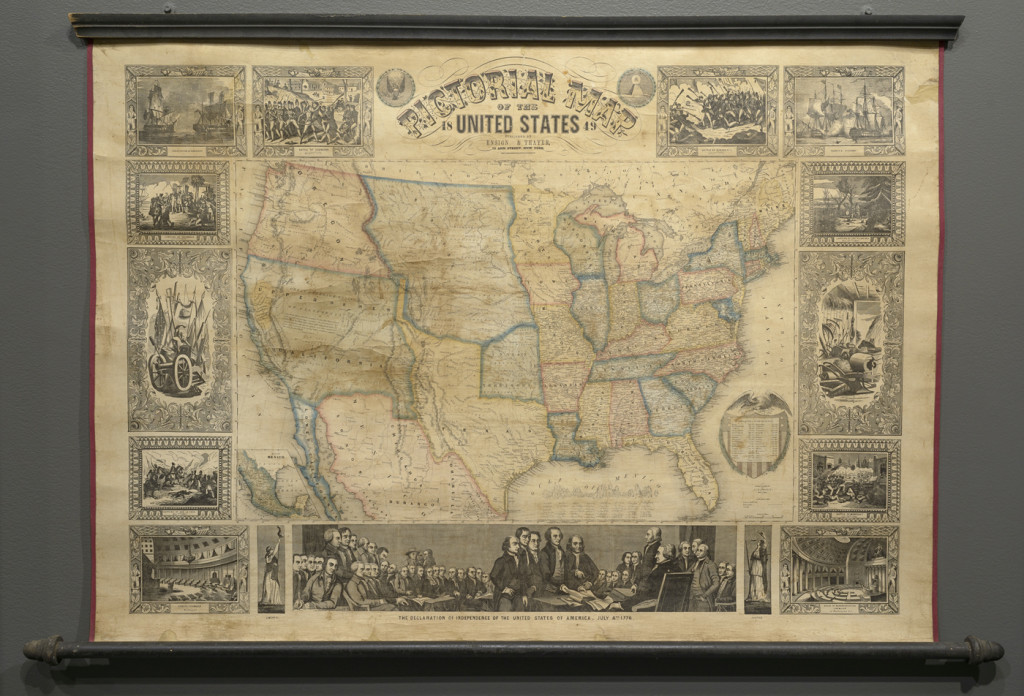

The Washington Map of the United States

Matthew Fontaine Maury

Published by H. G. Bond & Robert P. Smith

New York, New York; 1861

Lithograph and steel engraving

Collection of Barry MacLean

On the eve of the Civil War, colossal maps measuring on average seven-by-seven feet showed North and Central America. They were intended for public display in schools, offices, train stations, and city halls and showed the United States in full color by county. Matthew Maury’s map is unique because it contains information usually found only in books. While it depicts settlements, transportation routes, and county boundaries, inserted tables also show distances, state sizes and date of admission, miles of railroads, population, the breakdown of churches by denominations, and time differences. A series of diagrams depicts North American geology, climate, wildlife, food crops, plants and trees, and comparative topographic profiles of mountains and waterfalls. The decorative frame of the map, consisting of a ribbon and grapevine pattern, supports a gallery of portraits showing the first sixteen presidents. Abraham Lincoln can be seen in the lower right.

Maury’s name was dropped from the map in subsequent editions because of his support of the Confederacy, indicating that maps were frequently at the center of political and personal turmoil.

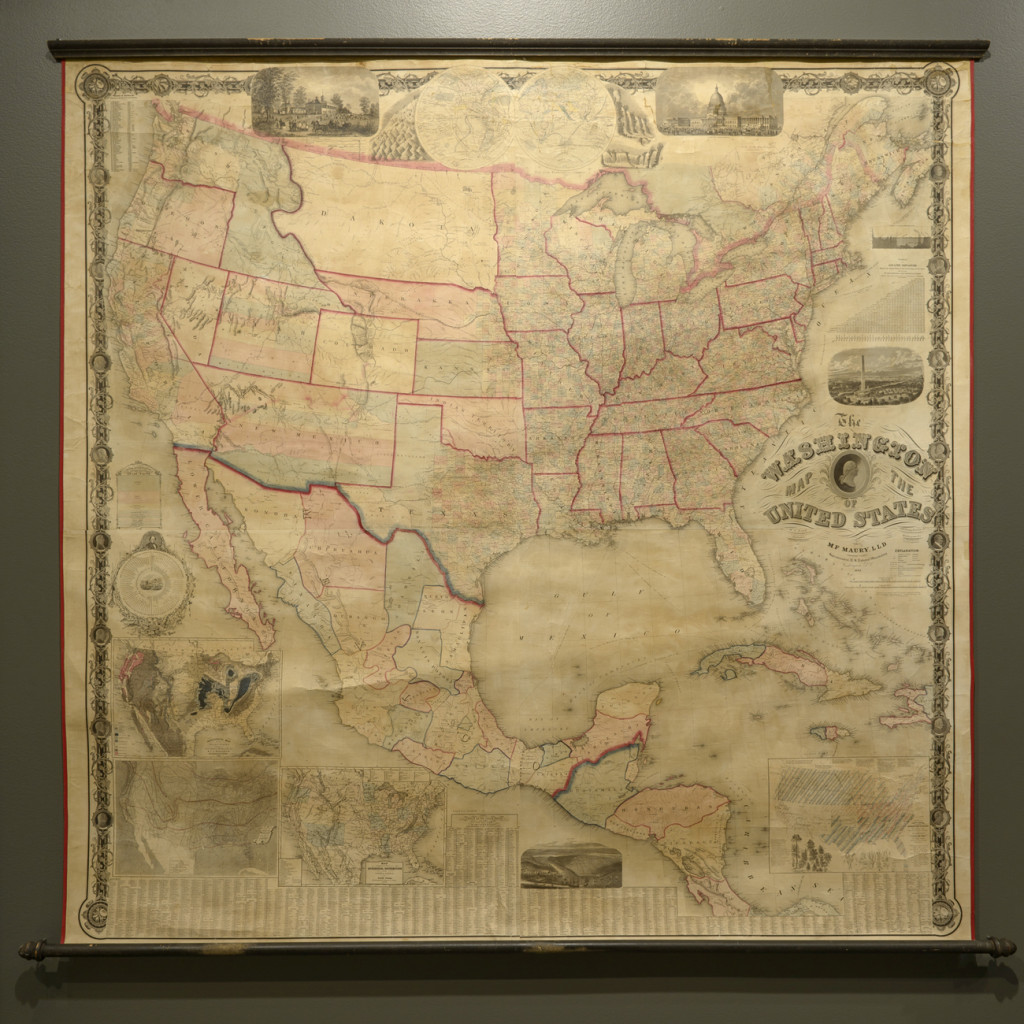

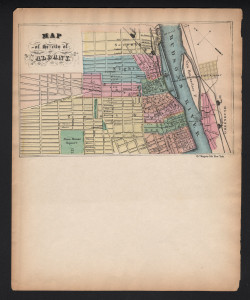

Map of the Counties of Barnstable, Dukes, and Nantucket, Massachusetts

(exhibited as photographic reproduction)

Surveyed by Henry F. Walling

Published by D. R. Smith & Co.

Boston, Massachusetts; 1858

Colored engraving on wove paper mounted on muslin

Pusey Map Collection, Harvard University Library

County maps depicting patterns of landholding and local geography emerged in the early 1800s. The product of private enterprise, they illustrated the ownership of all land parcels within the rural parts of a given county. The maps gained popularity because they catalogued the distribution and individual ownership of real property in an era of great population expansion, social mobility, and economic development.

Few details concerning the origins of this map are known, but we do know that roads were measured with a wheel odometer, pushed by a wheelbarrow-like device or drawn by horse and buggy. The map pinpoints the names and locations of every residence, workplace, church, and school. A typical mid-1850s price was $5 per copy. Prominent citizens allowed their names to be used in the map’s advertisements, testifying to the merits of the product while ensuring its financial success. Pictures of their homes could be added for a fee.

“We’re right over Illinois yet. And you can see for your-self that Indiana ain’t in sight.”

“I wonder what’s the matter with you, Huck. You know by the color?”

“Yes, of course I do.”

“What’s the color got to do with it?”

“It’s got everything to do with it. Illinois is green, Indiana is pink. You show me any pink down here, if you can. No, sir; it’s green.”

“Indiana pink? Why, what a lie!”

“It ain’t no lie; I’ve seen it on the map, and it’s pink.”

Conversation between Huckleberry Finn and Tom Sawyer during a balloon ride in Mark Twain’s Tom Sawyer Abroad (1894)

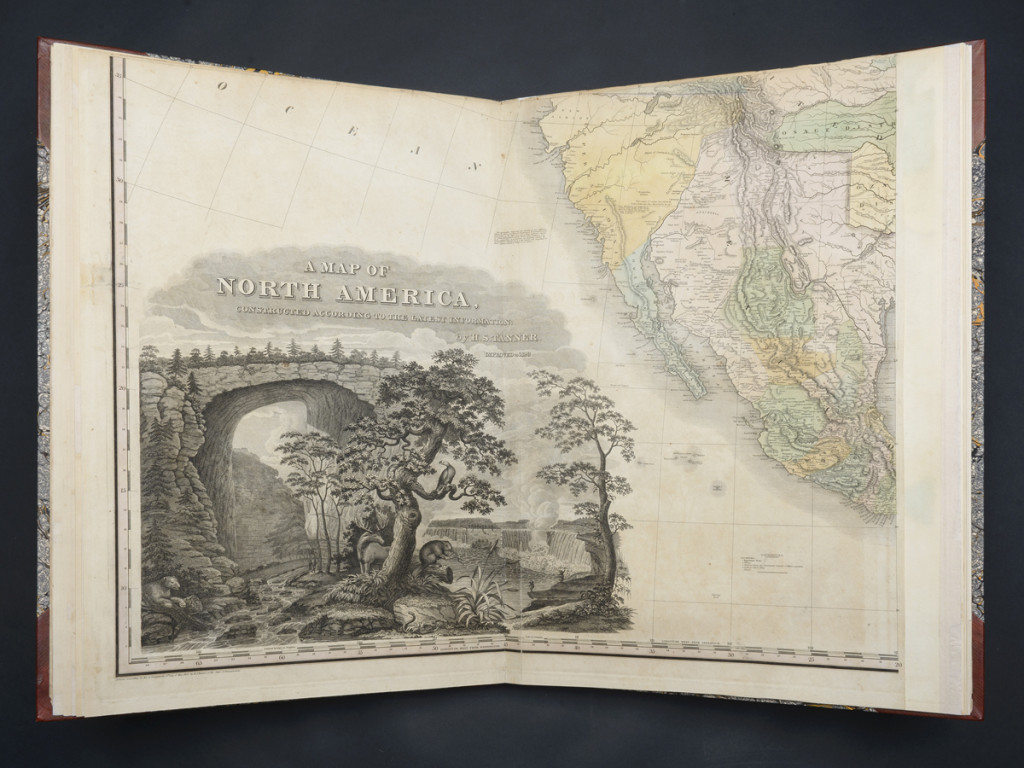

A New American Atlas

A New American Atlas

Henry Schenck Tanner

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; 1825

Collection of Barry MacLean

Henry Schenck Tanner’s drawing style affected the look of maps during the first half of the 1800s. Crisp lines and carefully spaced lettering not only made his maps more legible but transformed them into attractive display objects and even collectibles. When Tanner published his maps in the New American Atlas, his edition contained the most accomplished depictions of America yet to appear in print. Of the greatest importance were the maps showing the states. Highly detailed and brilliantly colored, states such as New York and Florida had their own dedicated page. Other double-page sheets showcased multiple states at a time.

To negotiate the high cost of production, the publisher issued the maps in five installments between 1819 and 1823. The public approved, and in April 1824, scholar Jared Sparks greeted the atlas enthusiastically as a “work to hold a rank far above any other.” Sponsors promoting the Mechanic Arts at the 1825 Exhibition of the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia wrote, “Mr. Tanner’s Maps are too well known to require any comment. His talents as a Geographer are only equaled by his enterprise as a publisher.”

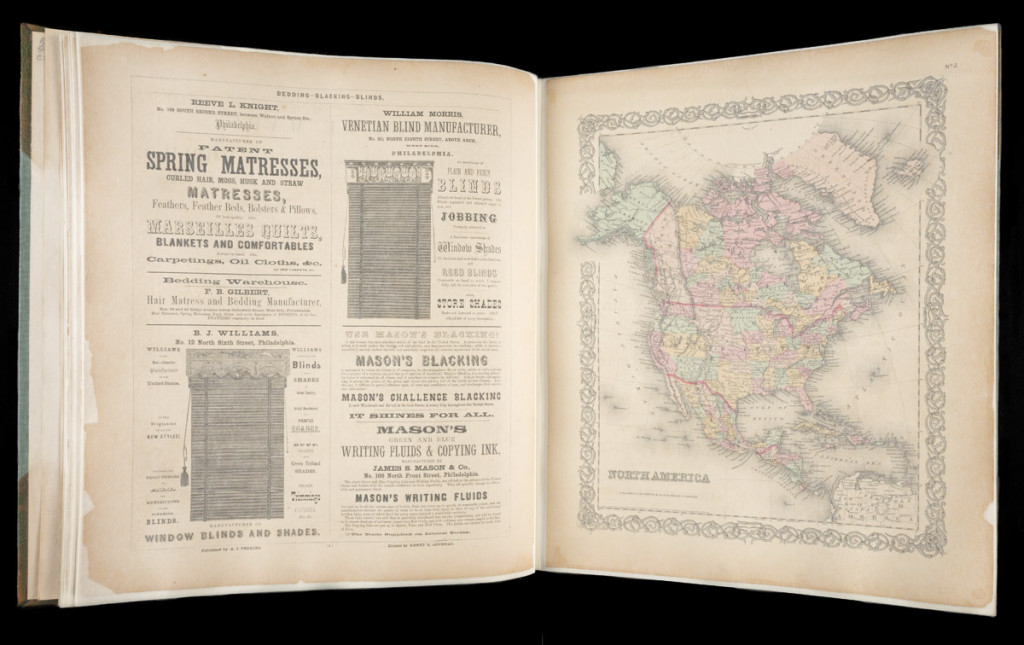

Colton’s Atlas of America

George Woolworth Colton

New York, New York: J. H. Colton, 1856

G1100 C72PF Printed Book and Periodical Collection, Winterthur Library

Called the “most beautiful atlas made in the United States” during the 1800s, Colton’s Atlas of America was a rare commercial edition. Half of the publication consists of advertisements promoting important businesses in North America, with special emphasis on Philadelphia. Heavily illustrated by elaborate wood engravings and lithographs, the ads depict manufactured goods, storefronts, factory halls, and foundries. To ensure the prominence of the atlas, Colton made the unusual investment of sending free copies to the country’s major hotels, stores, and even steamship companies on the condition that they “place this valuable work in some convenient place in your House, Steamer or Ship, accessible to your patrons.”

Often as I sit musing by the quiet fire, do my eyes seek the map which hangs upon the wall before me,—and as they rove over each familiar coast, they like many another adventurer of the times, suddenly dart away, . . . seeking a friend, yes a dear brother, who has gone before us to this golden shore.

Diary of Ellen Douglas Birdseye, January 26, 1851. Age 45

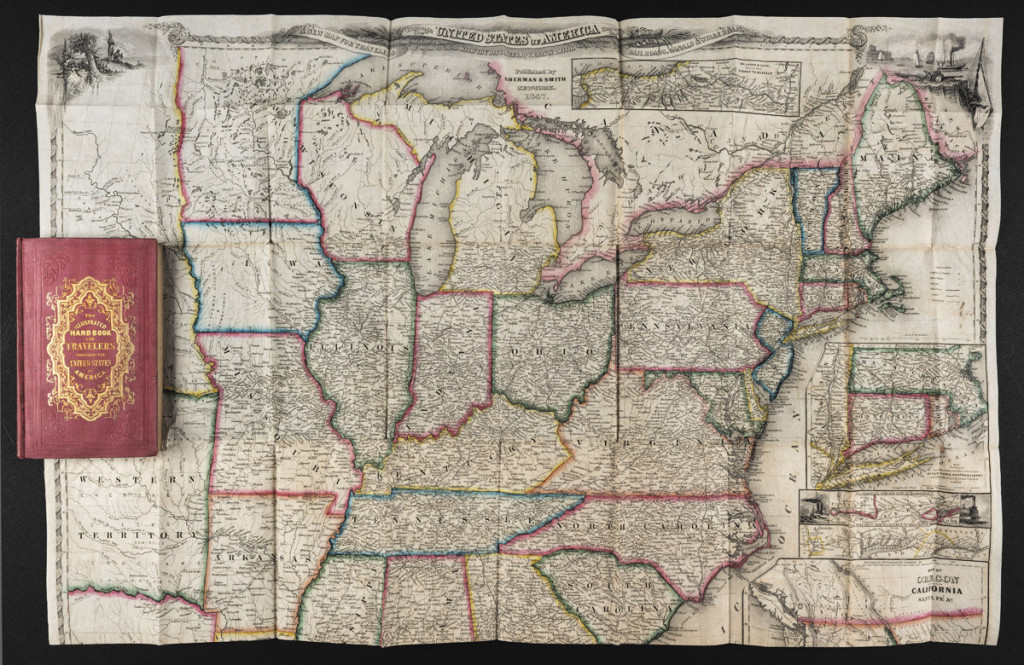

The Illustrated Hand-book: A New Guide for Travelers through the United States of America

John Calvin Smith

New York, New York: Sherman & Smith, 1847

E158 S66 Printed Book and Periodical Collection, Winterthur Library

The growth of the transport, tourist, and communication industries in nineteenth-century America affected the design of maps. Maps made for overland travelers up to the 1840s gave equal emphasis to roads, rail, and waterways. As railroads came to dominate the travel landscape, however, roads and canals disappeared from railroad maps. Catering to the needs of coach, rail, or steamship promoters, map publishers developed a cartographic style that contorted geography and scale in order to reflect a company’s interests but also take into account the travelers’ desire for identifying their location.

This selection shows the versatility of travel maps. They were conceived as portable objects ranging from the fold-out pocket map to the colored handkerchief map. Printed on envelopes or letterhead, map images playfully reminded the reader that they were essential for communication and transportation.

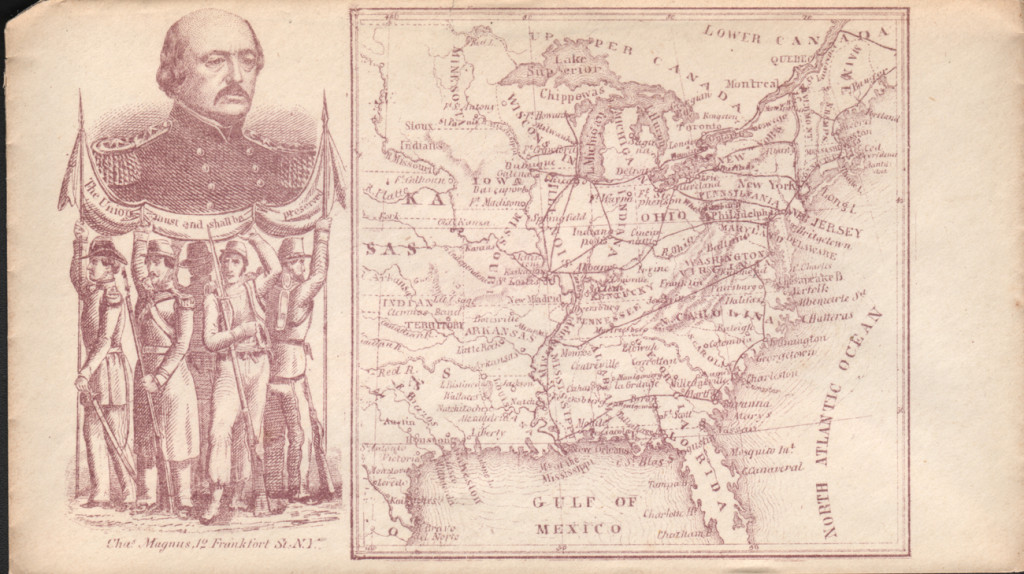

Envelope

Charles Magnus

New York, New York; 1861–65

71×016.6 Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, Winterthur Library

Letterhead

Charles Magnus

New York, New York; about 1855

94×70.2 Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, Winterthur Library

Map of the Circuit of Ten Miles around the City of Philadelphia (Handkerchief)

J. C. Sidney

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; 1847

Ink printed on silk

1987.133 Museum purchase

A person who is not qualified to teach geography, grammar, and geometry, and not well recommended for his morals, &c. is forbid, under heavy penalties by law, to take charge of a school.

Advertisement, “Massachusetts’ Schools,” Niles’ Weekly Register (1821)

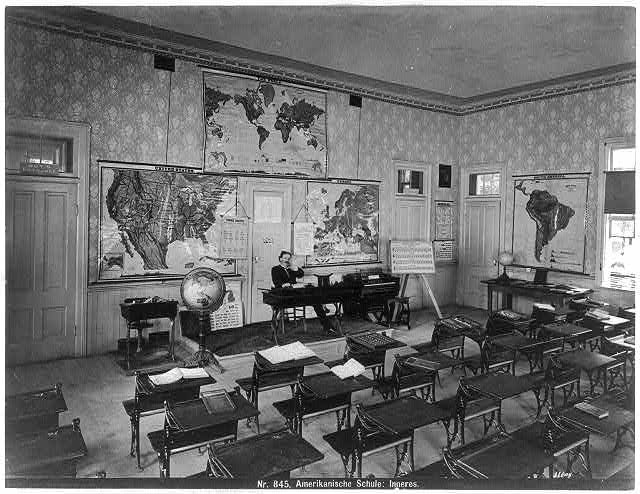

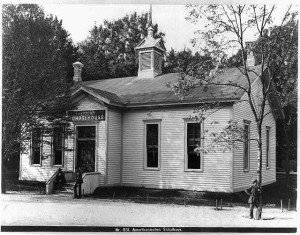

American rural schoolhouse room and exterior

American rural schoolhouse room and exterior

Universal Exhibition of Vienna, 1873

(exhibited as photographic reproduction)

Printed by J. Löroy

Library of Congress

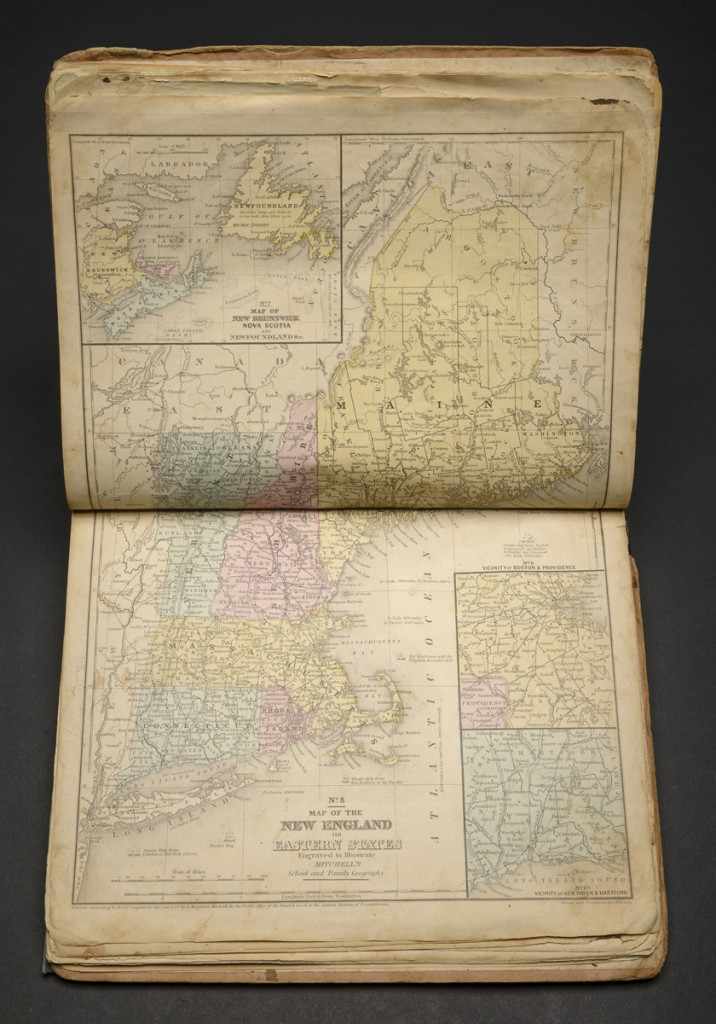

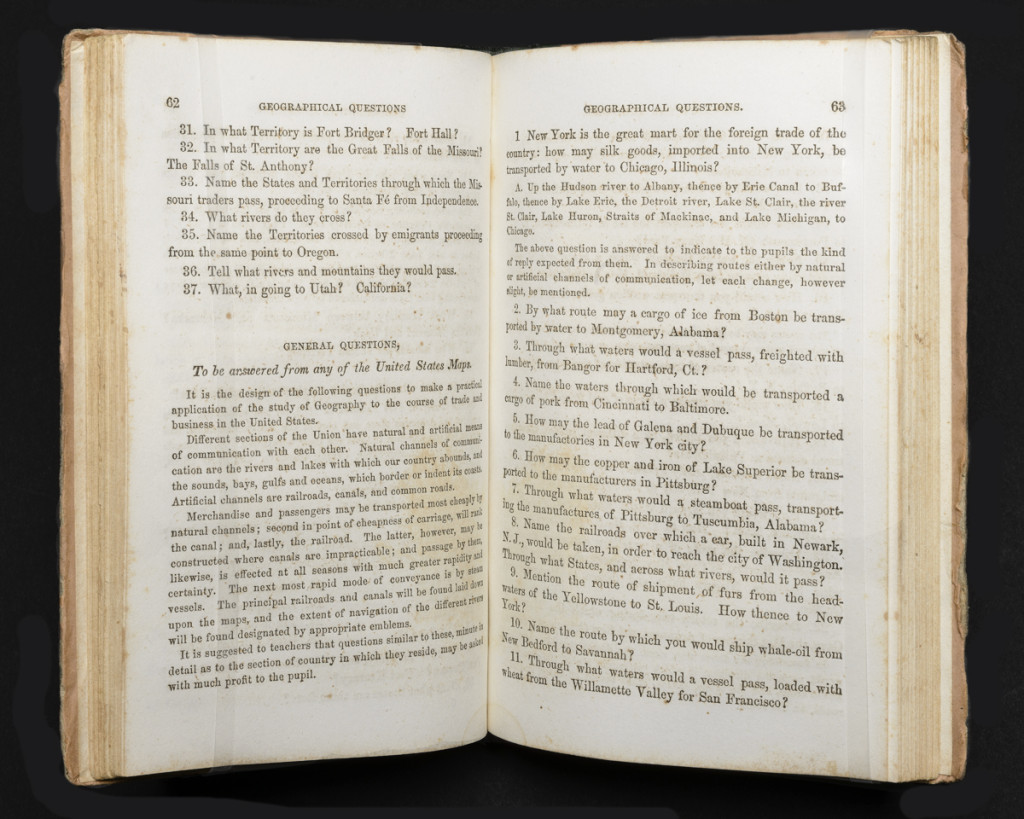

Although American colleges eliminated geography from their curriculum during the 1810s and 1820s, they retained map knowledge as part of the entrance examination. This change pushed map instruction into the lower educational levels. As a result, business leaders, teachers, and parents lobbied for the permanent inclusion of geography and mapmaking in primary and secondary schools. Thanks to the inexpensive school atlas and geographical question book, students across the nation embarked on lessons dominated by the recital of place names and exercises in map drawing and coloring. That maps had become synonymous with American democratic culture was the message sent by the United States when submitting the “American rural schoolhouse room” to the Universal Exhibition of 1873, hosted in Vienna, Austria.

Mitchell’s School Atlas

Samuel Augustus Mitchell

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: E. H. Butler & Co, 1861

G125 M68 Printed Book and Periodical Collection, Winterthur Library

Mitchell’s Geographical Question Book

Samuel Augustus Mitchell

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: E. H. Butler & Co., 1860

G131 M68 S Printed Book and Periodical Collection, Winterthur Library

Geography being now esteemed an essential part of General Education, no expense is spared in procuring books and maps to facilitate the study.

Rembrandt Peale, Graphics, the Art of Accurate Delineation (1850)

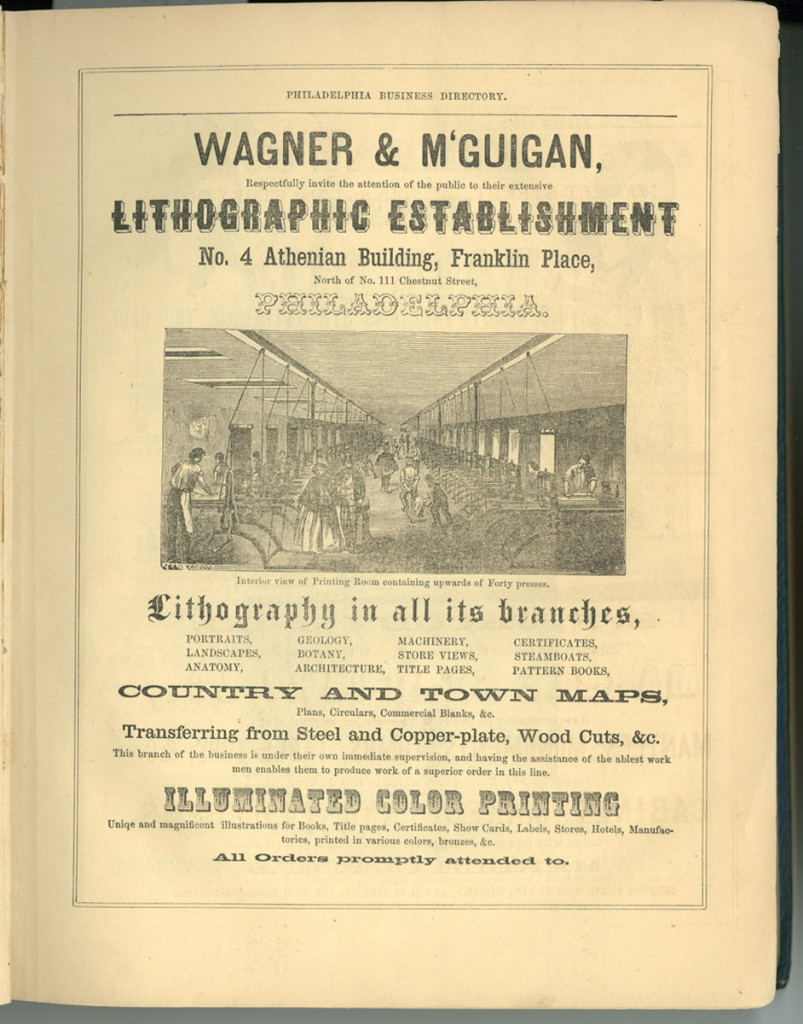

Wagner & McGuigan’s Lithographic Establishment

(exhibited as photographic reproduction)

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; 1847

Harry T. Peters America on Stone Collection, Library Company of Philadelphia

The Industrial Revolution changed map production and consumption on a grand scale. Map publishers employed a workforce consisting of authors, compilers, draughtsmen, and engravers working on copper, steel, wood, and stone. With the introduction of steam power, printers increased their output from twelve prints  per hour to nearly one thousand during the 1820s and 1830s. Millions of maps were produced on a single day after the invention of the rotary press in 1843. The enormous output forced a greater standardization in titles, image size, and coloring. In the world of retail, newspapers were full of ads announcing the latest map or atlas, including a railroad map measuring 25-by-17 feet. After the Civil War, map shops emerged all over the country, staging goods to attract window shoppers. At the 1876 Centennial International Exhibition in Philadelphia, maps were prominently featured in exhibits devoted to American books and the art of printing.

per hour to nearly one thousand during the 1820s and 1830s. Millions of maps were produced on a single day after the invention of the rotary press in 1843. The enormous output forced a greater standardization in titles, image size, and coloring. In the world of retail, newspapers were full of ads announcing the latest map or atlas, including a railroad map measuring 25-by-17 feet. After the Civil War, map shops emerged all over the country, staging goods to attract window shoppers. At the 1876 Centennial International Exhibition in Philadelphia, maps were prominently featured in exhibits devoted to American books and the art of printing.

A. S. Barnes & Co. Book Department, Main Building

1876 Centennial International Exhibition

(exhibited as photographic reproduction)

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; 1876

Free Library of Philadelphia

Wagner & McGuigan’s Lithographic Establishment

(exhibited as photographic reproduction)

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; 1847

Harry T. Peters America on Stone Collection, Library Company of Philadelphia

Advertisement

(exhibited as photographic reproduction)

The Ohio Statesman

Columbus, Ohio; December 24, 1841

NewsBank

In every house and shop, an American map has been unrolled, and daily studied, and now that peace has come, every citizen finds himself a skilled student of the condition, means, and future, of this continent.

Ralph Waldo Emerson, Journals and Miscellaneous Notebooks (1865)

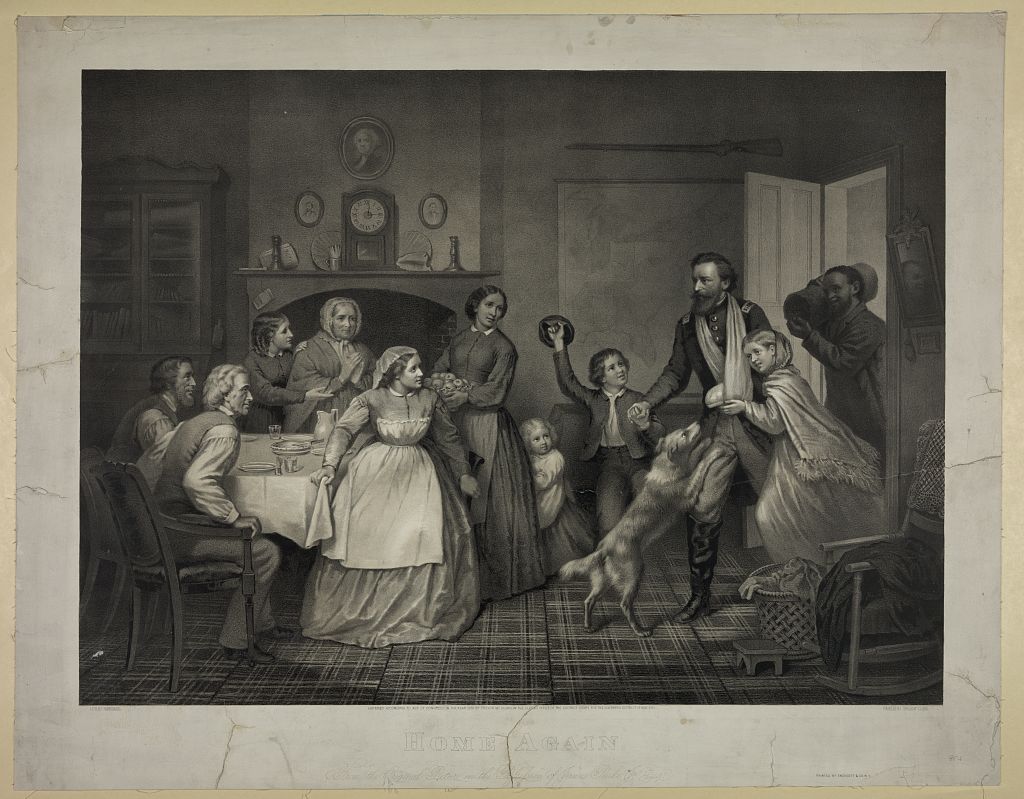

Home Again

Dominique Fabronius, after a painting by Trevor McClurg

Printed by W. Endicott & Co.

New York, New York; about 1866

Lithograph

Library of Congress