Indoors/Outdoors: Men and Their Maps

Historically, maps have been considered the province of men. In America it wasn’t monarchs and ministers but farmers and merchants who depended on them to govern and stay connected. For men, maps were an integral part of private life. Displayed in studies and libraries, they shaped masculine attitudes toward reading, writing, and interior décor. They were also essential tools for outdoor activities such as travel, surveying, or landscaping. Above all, circulating in a culture in which social status was defined by land ownership, maps were at once useful and symbolic objects illustrating male identity and self-worth.

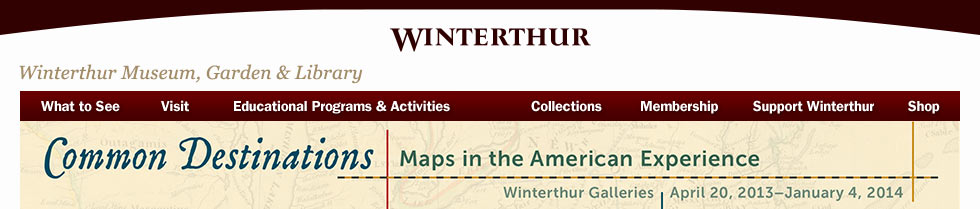

Map of the City and Liberties of Philadelphia

Drawn by John Reed

Engraved by James Smithers

Printed by Thomas Man

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; 1774–86

Line engraving on linen

1961.238 Museum purchase

Local maps, ranging from town plans to rural estate maps, performed vital economic and cultural functions for property owners until the end of the 1800s. Designed for Philadelphia residents, John Reed’s Map of the City and Liberties of Philadelphia combined usefulness with art. The six sheets show the city and its suburbs, including the surveyed lots of undeveloped land in the northern “liberties.” The map provided a panoramic directory that served groups such as merchants, tax collectors, and real estate agents. The decorative cartouche and engraved views of the Alms House, Pennsylvania Hospital, and State House associated the map with popular pictures of the time. Printed on linen rather than paper, the map was a versatile, multipurpose object.

Ackermann’s Repository of Arts, Literature, Commerce, Manufactures, Fashions, and Politics

London, England: Rudolph Ackermann, 1811

AP4 R42 Printed Book and Periodical Collection, Winterthur Library

The man of good taste turned to advice books in order to study the “Do’s and Don’ts” of domestic architecture. Rudolph Ackermann and other authors of advice literature for men frequently recommended the display of maps and globes in offices and studies—spaces associated with male privacy. The maps were to be placed strategically, so as to enhance and balance the ensemble of furniture with decorative objects. With proportion and propriety ruling the design, the display of wall maps signified personal knowledge and the virtue of gravitas, two attributes valued in men.

[Above image portrays landscape after alterations. See below for “before.”]

Observations of the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening

Observations of the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening

Humphrey Repton

London, England: T. Bensley, 1803

SB471 R42* Printed Book and Periodical Collection, Winterthur Library

As landscape gardening came of age in the early United States, the well-heeled as well as middle-class landowner sought out design and pattern books. The most popular ones involved before-and-after views, illustrating how changes in topography or vegetation allowed a countryseat or suburban home to become integrated into the landscape. While these views followed plans formulated by aesthetic theories such as the picturesque style, each called for the ability to read map drawings in order to interpret changes to the land.

Portrait miniature

United States; 1820–30

Watercolor on ivory

1957.589a Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont

Maps and globes were popular props in portraits and genre paintings throughout the 1700s and 1800s. A map showing the United States could signal a sitter’s economic station, educational accomplishment, and national identity. This portrait miniature depicts a well-dressed man seated at a desk surrounded by the tools of his profession—the telescope, chart, globe, hourglass, compass, sextant, and pencil—identifying the sitter as a member of the merchant marine.

Terrestrial globe with stand

J. Wilson & Sons

Albany, New York; 1825

Ink and gesso on paper and wood, brass

1969.460.2 Gift of Mrs. Alfred C. Harrison

Terrestrial and celestial globes were important components of a gentleman’s study during the 1700s and early 1800s. By the 1820s, the manufacture of terrestrial globes increased substantially, with furnishing and publishing houses offering versions from 6 to 30 inches in diameter. Stands or partial frames for the globes were custom-made to match the architecture of studies and office spaces.

The Tools of Surveying

Land was perhaps the most common commodity owned and traded by Americans of all ranks in the colonial and early national period. Because land ownership determined individual wealth, social rank, and taxes, it was in a landowner’s interest to be a skilled surveyor. From the early 1700s onward, tutors and evening schools offered surveying lessons to semi-literate farmers in addition to well-read gentlemen, teaching technical terms, geometry and algebra, and the art of mapmaking. The results of a land survey consisted of a field book (a record of all measurements) and a plat (a map showing the surveyed land). Land surveying provided a steady—even lucrative—job for young men, including future presidents George Washington and Abraham Lincoln as well as naturalist and philosopher Henry David Thoreau.

Surveying compass

Probably made by Benjamin Rittenhouse and William L. Potts

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; 1750–75

Brass, wood, glass

1957.646a-e Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont

Drafting instruments and case

England; 1790–1840

Shagreen, wood, brass, iron, paper

1964.1044a-j Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont

Tripod

Tripod

Nottingham, Pennsylvania; 1790–1813

Wood, brass, iron

2003.58 Gift of the McCauley Family

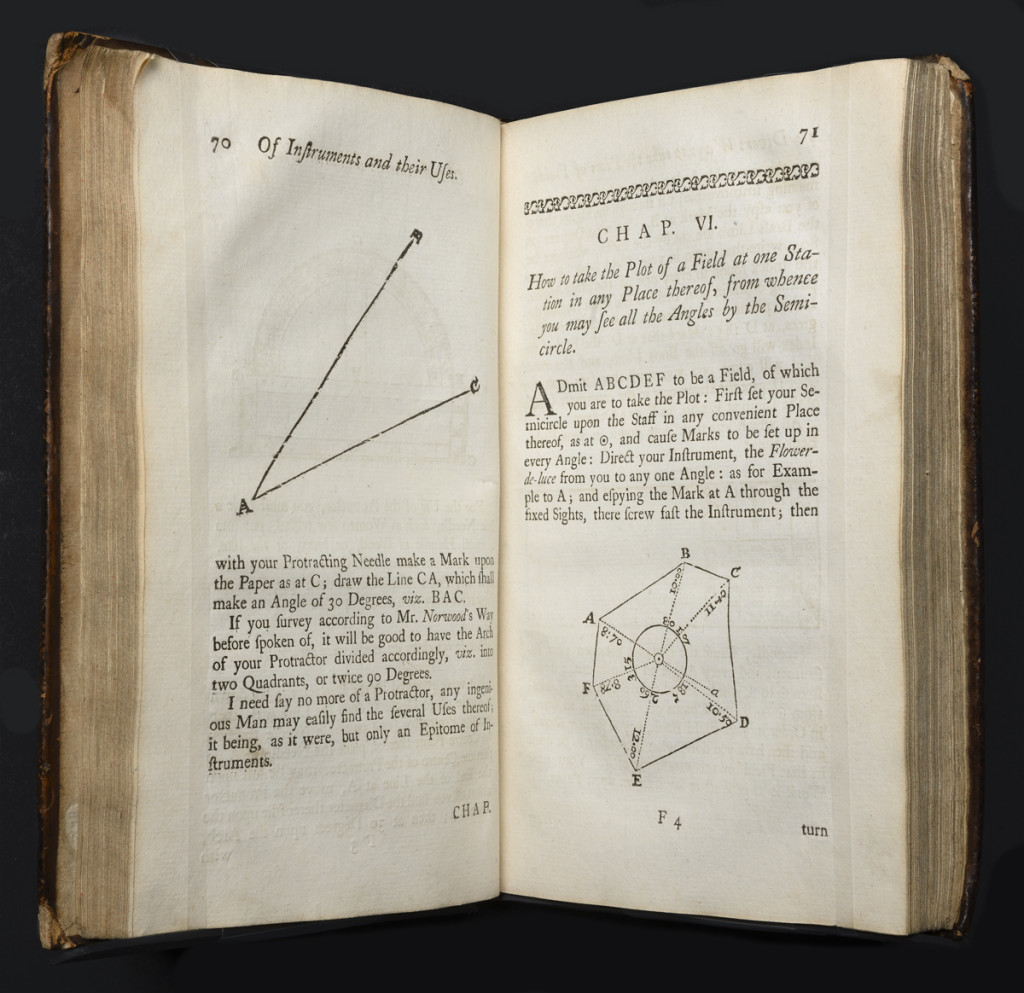

Box with measuring tape

United States; 1790–1810

Paper, linen, metal

1954.12.1 Museum purchase

Chart case

United States; 1800–1875

Tinned sheet iron filled with sand

1969.672a,b Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont

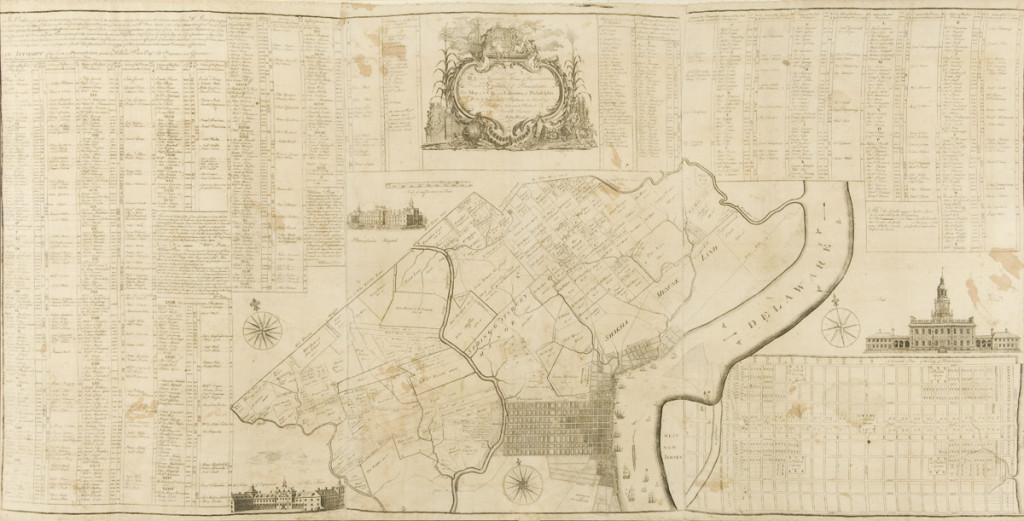

Geodæsia: or, The Art of Surveying and Measuring of Land, Made Easy

John Love

London, England: W. Innys & J. Richardson, 1753

TA544 L89 Printed Book and Periodical Collection, Winterthur Library

In addition to taking classes, farmers and landowners could study the art of surveying with the help of how-to manuals. At the time of the American Revolution, there were more than a dozen textbooks in circulation, teaching the basics of geometry and trigonometry, the method of surveying land by compass and chain, and the art of writing and “polishing” (coloring) a map. John Love’s handbook, Geodæsia, published in 1688 and still in use in 1800, was one of the first manuals to specifically address surveying practices in North America. Because there were not many church steeples to provide long-distance views for taking measurements, American surveyors did their work on foot, cutting through vast forests and wading through snake-infested swamps.

Land survey of New Castle County

Drawn by Isaac Stevenson

New Castle County, Delaware; 1803

Ink and watercolor on laid paper

1957.642a,b Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont

The final product of a land survey was a rudimentary map called a plat. It usually consisted of a single sheet bearing the outline of the land and an account of the directions and measurements. Beginning with the early 1700s, such plats emerged as an important tool for assessing and recording property values, taxes, and rents across the former colonies and future states. Because plats served as proof of property and as a form of estate map (delineating residential areas, arable land, woods, and wasteland), they quickly became a standard feature of the American economy. They were so popular that Benjamin Franklin compared them in 1729 to paper money, calling them “coined land.”