Sociable Maps: Parlors and Pubs

Maps were a visible and vital part of social life in early America. They could be found hanging in taverns, shops, town halls, and train stations. In private homes they were more abundant, especially among the affluent and middle class. Placed in high-traffic areas such as parlors, dining rooms, and hallways, maps occupied spaces reserved for rituals of conviviality. In such settings, they fostered dialogue among friends and strangers, prompting people to ask for directions, engage in polite conversation, test geographic knowledge, play geographical games, or, as illustrated by the Washington family, to simply enjoy one another’s company.

The Washington Family

Edward Savage

United States; 1798‒1805

Oil on panel

1961.708 Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont

In this family portrait, George Washington poses with the plan of the District of Columbia. Originally painted on a nine-feet-wide canvas to show “The President and Family, the full size of life,” the map underscores Washington’s symbolic status and his commitment to the nation’s new capital. Spread across the table like a tablecloth, it also tells a second story. As the family studies and touches the map, it becomes the material link connecting George Washington to his wife, Martha Custis, and his step-grandchildren, Eleanor and George.

The pretty flower’d wall paper in the hall is all cover’d over with nothing but maps, and drafts, and charts.

A wife’s complaint in “Frettana,” Columbian Magazine (1787)

The Trimble Family

Auguste Edouarte

New York, New York; 1842

Ink and paper on paper

1954.4.2 Gift of Henry Francis du Pont

In American homes, families encountered maps in an array of different formats but usually with a similar purpose: to instruct and entertain. Prominently displayed on walls along with mirrors and prints or discreetly placed on shelves, desks, and worktables, maps defined the visual experience of the home. As popular household objects, they encouraged members of the family to engage with them in serious study or playful exchange.

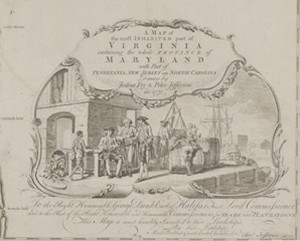

Wall maps in particular were prized possessions between 1750 and 1850. Typically put on display in the best rooms of the home—the parlor and dining room—they invited inspection by all members of the household, including guests, servants, and slaves. Celebrated for its geographic accuracy and neat engraving style, A Map of the Most Inhabited Part of Virginia by Joshua Fry and Peter Jefferson was not only one of the more popular wall maps before the Revolution but turned into a prized collectible in the subsequent decades. For many owners, it served as a status symbol, signifying the virtues of Enlightenment science, knowledge of the world, and good decorative taste.

A Map of the Most Inhabited Part of Virginia

A Map of the Most Inhabited Part of Virginia

Drawn by Joshua Fry and Peter Jefferson

Engraved and expanded by Thomas Jefferys

Published by Robert Sayer and John Bennett

London, England; 1775

Line engraving and etching with watercolor on laid paper

1963.118a,b Museum purchase

The Fry-Jefferson cartouche depicts the Atlantic tobacco trade, illustrating the complex relationship among maps, commercial activities, and social customs. It shows merchants celebrating the sale of goods manufactured by slaves. Once placed in parlors and dining rooms, the cartouche gives testimony to this exchange in domestic settings. As map owners sat down to discuss or admire the map over a glass of port or cup of tea, they were reminded of the sources of their wealth even as they were being served by slaves or household staff.

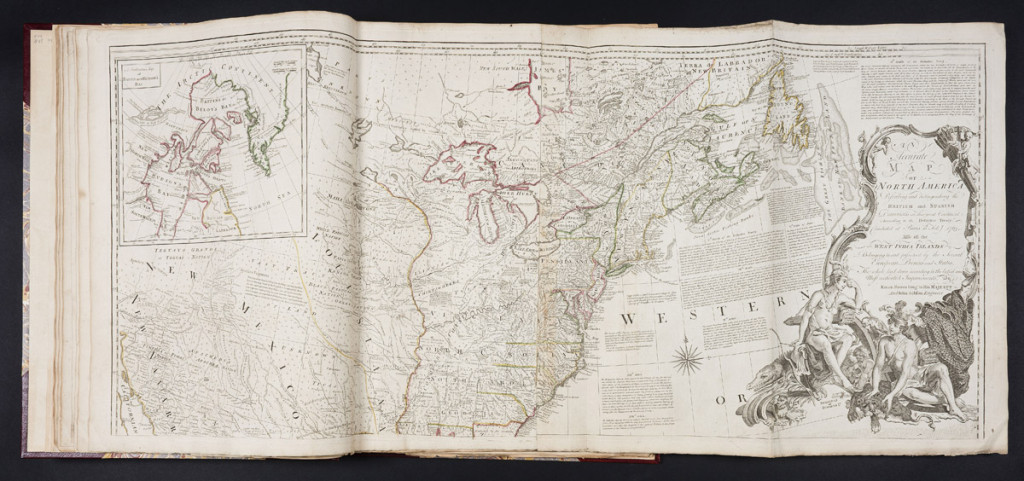

The American Atlas; or, A Geographical Description of the Whole Continent of America

Thomas Jefferys

London, England: Robert Sayer and John Bennett, 1775

E14 J45 PF Printed Book and Periodical Collection, Winterthur Library

The American Atlas, published by Thomas Jefferys, was the Cadillac of atlases sold in early America. At a cost of £2 sterling (roughly £200 or $314 today), it weighed twelve pounds and expanded to fifty inches when individual maps were unfolded. A valuable and impressive possession, it was intended for gentlemen’s studies and libraries. Owners liked to show their atlases on dinner or side tables to better examine the maps during social events or parlor games. Many atlas maps reveal traces of being conversation pieces or a source of personal reflection. The letter X marks many spots, and lines made by pen or pencil might track family journeys or famous voyages such as Captain Cook’s South Sea explorations or the trail of the Lewis and Clark expedition.

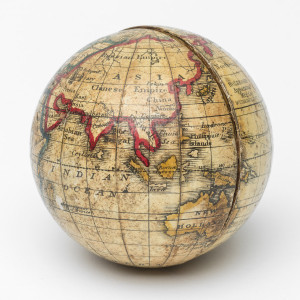

Pocket globe

Pocket globe

Holbrook Apparatus Manufacturing Co.

Wethersfield, Connecticut; 1830–59

Line etching with watercolor on paper and wood

1967.522 Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont

Pocket-size globes were novelty objects from the 1700s to the mid-1800s. Measuring three to five inches in diameter, they fulfilled social rather than practical functions since their size made accurate calculations impossible. Initially a status symbol for gentlemen, pocket globes eventually became an educational toy for children. When painted with references to historic voyages or battle sites, they served as patriotic objects celebrating national identity. Considering that in 1855 alone the Ohio State Commissioner purchased 11,987 Holbrook Company globes, public schools and their pupils became some of the primary consumers of maps and were responsible for their introduction into American homes.

The act of combining these [map] parts exercises and amuses the mental faculties; and the study of Geography thus made attractive is rapid and permanent in its results; and more knowledge of the subject is acquired in one hour spent in this intellectual amusement than in a month of hard book-study.

Advertisement for Colton’s Geographical Combination Map (1855)

A New Map of Europe

Sold by John Wallis

London, England; about 1800

76×198 Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, Winterthur Library

Early American table games included map puzzles, also called “dissected maps.” They were advertised as early as 1786, having been invented in 1760 by Englishman John Spilsbury, who mounted a printed map on a thin piece of wood and then cut it into pieces. Map puzzles joined other board games and were popular throughout the 1800s in American homes.

The Elements of Astronomy and Geography

The Elements of Astronomy and Geography

Abbé Paris

London, England: John Wallis Co., 1795

72×357 Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, Winterthur Library

Geographical study cards supplemented the array of maps found in American homes. Students used cards like The Elements of Astronomy and Geography for rote learning exercises demanded by early schoolbooks. The cards also provided the backbone for parlor games such as “City-Country-River,” in which participants had to remember geographical names, coordinates, and definitions with the aid of maps, globes, and textbooks.

[Please, click above images to see full cards.]

The Postmaster very civilly invited me into his parlour, to settle for the postage, where seeing a large map, I took the opportunity of tracing my journey, which the postmaster observing, he politely assisted me in it, pointing out the most proper route.

Mr. Fortescue Cuming, Tour to the Western Country (1807)

Village Tavern

John Lewis Krimmel; 1813‒14

(exhibited as photographic reproduction)

Oil on canvas

Toledo Museum of Art (Toledo, Ohio), Purchased with funds from the Florence Scott Libbey Bequest in Memory of her Father, Maurice A. Scott, 1954.13

Photo: Photography Incorporated, Toledo

Maps were fixtures in American public houses between the Seven Years’ War (1756‒63) and the Civil War (1860‒65). They were posted on walls next to newspaper racks and train schedules in taverns, coffee houses, and inns. Many public houses sold maps in addition to geographic playing cards and satirical prints mocking politicians and their lack of geographical knowledge. Maps also provided the backdrop for conversations about road conditions, family property, travel plans, and, during times of national crisis, the theaters of war.

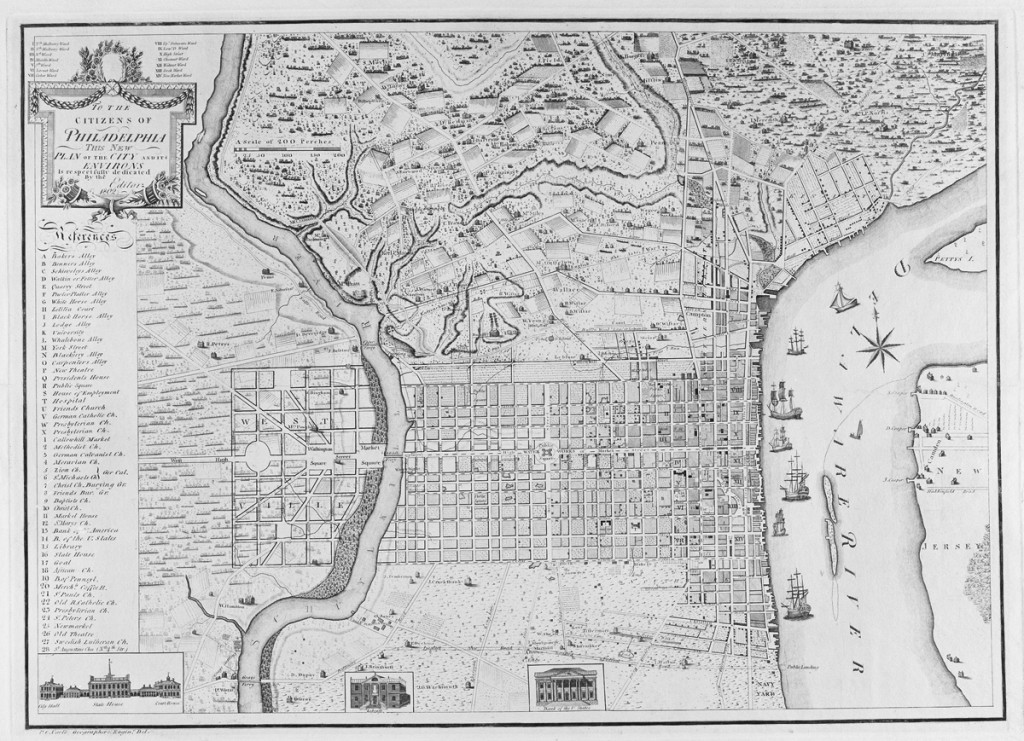

Plan of the City of Philadelphia and Environs

Drawn by Pierre Charles Varlé

Engraved by Robert Scot

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; 1802

Engraving on laid paper

1960.358.1 Museum purchase

Like many others from the eighteenth-century, the Varlé map aspired to merge the Enlightenment ideals of knowledge and idealism. The city map takes stock of existing topography while introducing speculative designs for future land development. Map readers had to rely on visual cues, official handbooks, personal knowledge gained from previous travels, word of mouth, and common sense to comprehend and navigate the map. Although it shows city landmarks that never came to fruition—such as Washington Square in the “West Ville” section of Philadelphia—the map correctly identifies many of the major transportation routes that allowed goods, people, and information to travel between the city and country in the early 1800s.

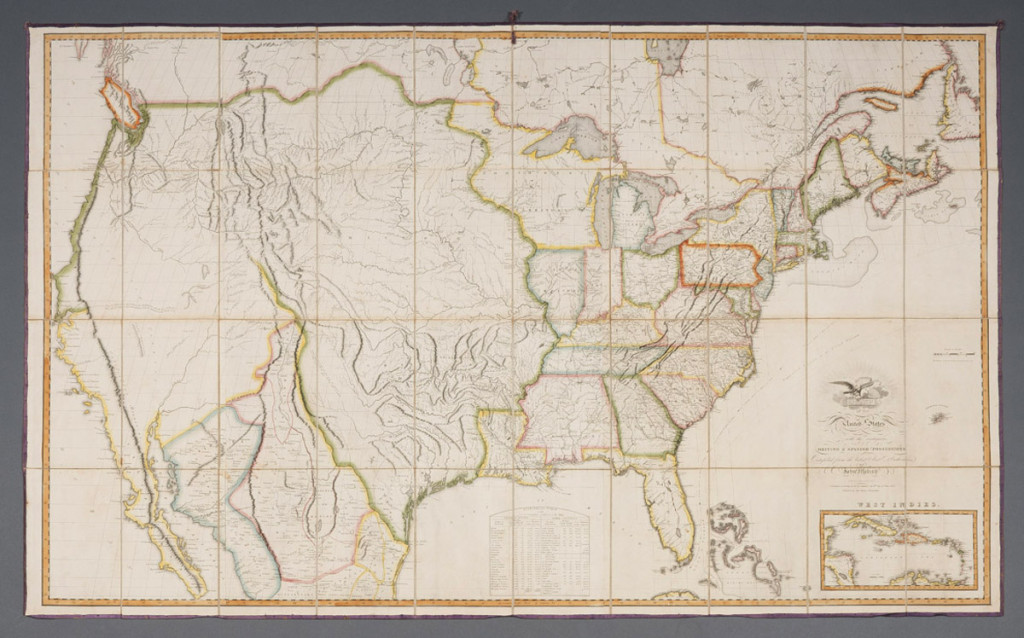

Map of the United States, with the Contiguous British and Spanish Possessions

John Melish

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: J. Melish, 1816

E165 M52g Printed Book and Periodical Collection, Winterthur Library

John Melish’s Map of the United States, published shortly after the War of 1812, was hugely influential during the postwar years. It was one of the first maps to print the outcomes of the Treaty of Ghent and show the United States territory stretching from coast to coast. It was consulted during the debate that ended with the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which allowed Missouri to enter the Union as a slave state along with Maine as a free state. It was also perhaps the best-known map during congressional deliberations that resulted in the Monroe Doctrine, a policy introduced in 1823 stating that any efforts by European nations to colonize land or interfere with states in North or South America would be viewed as acts of aggression requiring intervention by the United States.

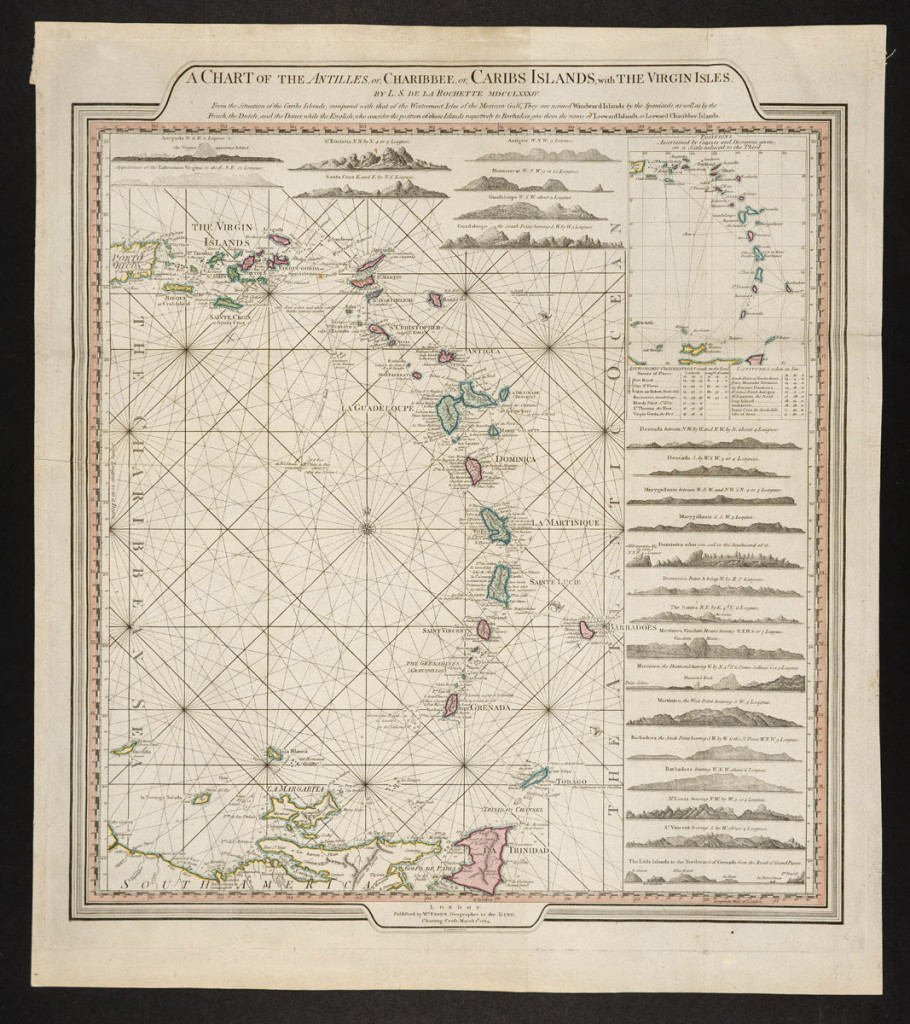

A Chart of the Antilles

Drawn by Louis Stanislas d’Arcy Delarochette

Engraved by W. Palmer

Published by William Faden

London, England; 1784

Etching and engraving with watercolor on wove paper

1961.423 Gift of Mrs. G. Brooks Thayer

Pilot charts were integral to life along the coast. Harbormasters, shipping offices, and even tavern-keepers displayed such maps for sailors, merchants, and others concerned with navigating rocks and shoals when sailing the Atlantic Coast and rivers. A crisscross network of rhumb lines (those marking a ship’s intended path based on a defined bearing) provided direction to the navigator when on the high seas. Sea charts listed coordinates of islands, soundings of coastal water depths, and the course of tides. Topographical sketches profiling mountains offered a visual aid for identifying port entrances and river mouths.

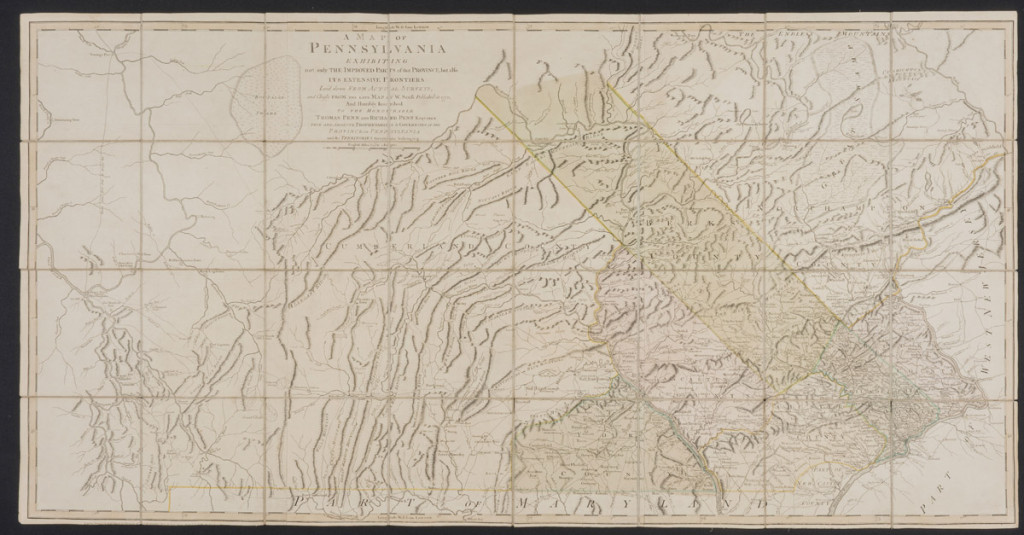

A Map of Pennsylvania

A Map of Pennsylvania

Published by Robert Sayers and Richard Bennett

London, England; about 1775

Etching with watercolor on laid paper and linen

2001.35a,b Gift of Charles A. Fagan III

As American road networks expanded, so did the production of case and pocket maps. By folding and boxing up existing wall and atlas maps, publishers discovered a profitable market niche. Pocket maps were designed to fit into coat pockets for men and tie-on pockets for women. Often tipped into travel guides for emigrants in the early 1800s, they fulfilled a variety of functions—offering directions, information about places and distances, conversion tables for American currencies, and ample space for personal notes and memories.

Liberty Triumphant; or, the Downfall of Oppression

London, England; 1774

Etching and engraving on laid paper

1957.1264 Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont

Patrons of public houses, especially coffee houses, regularly found satirical prints on walls and tables during the 1770s and 1850s. An early form of political commentary, these prints frequently incorporated maps or map-like images in order to skewer represented parties and entertain audiences. Anonymously published in 1774, Liberty Triumphant tells the story of the American rebellion (right) against a divisive British government (left).

A crestfallen Britannia utters her distress about the misconduct of the colonies. Facing her across the Atlantic Ocean is North America and the Goddess of Liberty. An Indian Princess, armed with bow and arrow and supported by her braves, protectively stands before the Liberty Tree; at their feet, a group of Loyalists lament the loss of income and influence as a result of the American boycott of English goods. Significantly, all action takes place on a map, thus providing fodder for commentary among the geographically self-conscious colonists (especially for those who realized that the map has us view America upside down).

Powder horn

Powder horn

Carved by Daniel Roberts

New York, New York; 1757–60

Incised cow horn

1958.1000 Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont

Powder-horn maps were a vernacular tradition unique to the Seven Years’ War and the Revolutionary War. They were engraved by soldiers for both practical and sentimental reasons. Because much of North America was uncharted territory, powder horn maps were personal records of geographical information. The one carved by Daniel Roberts features the Hudson River and its tributaries. It enumerates towns along the waterways and shows major landmarks such as Lake Oneida. Kept close to the body, a powder horn map was a document for recalling battles or, as suggested by the royal crest, for demonstrating the owner’s allegiance to the British king.