The National Map, 1784‒1815

American map culture changed dramatically after the Revolution. Following the Peace of 1783, citizens demanded more maps showing North America and the new nation, and entrepreneurs responded in kind. In 1790 alone, more than 90 percent of the maps made in the United States depicted only the nation’s territory. By 1800, the image of the national map had become an easy-to-recognize logo decorating textile prints, furniture, and paintings. A powerful symbol of political unity, it was used as a metaphor in the Federalist Papers (1787/88) and in President Washington’s “Farewell Address” (1796). Orations, sermons, and novels referenced the national map when debating American history or the nation’s character. For many citizens—ranging from statesmen to farmers, ministers to schoolgirls—it was the key for building a new society.

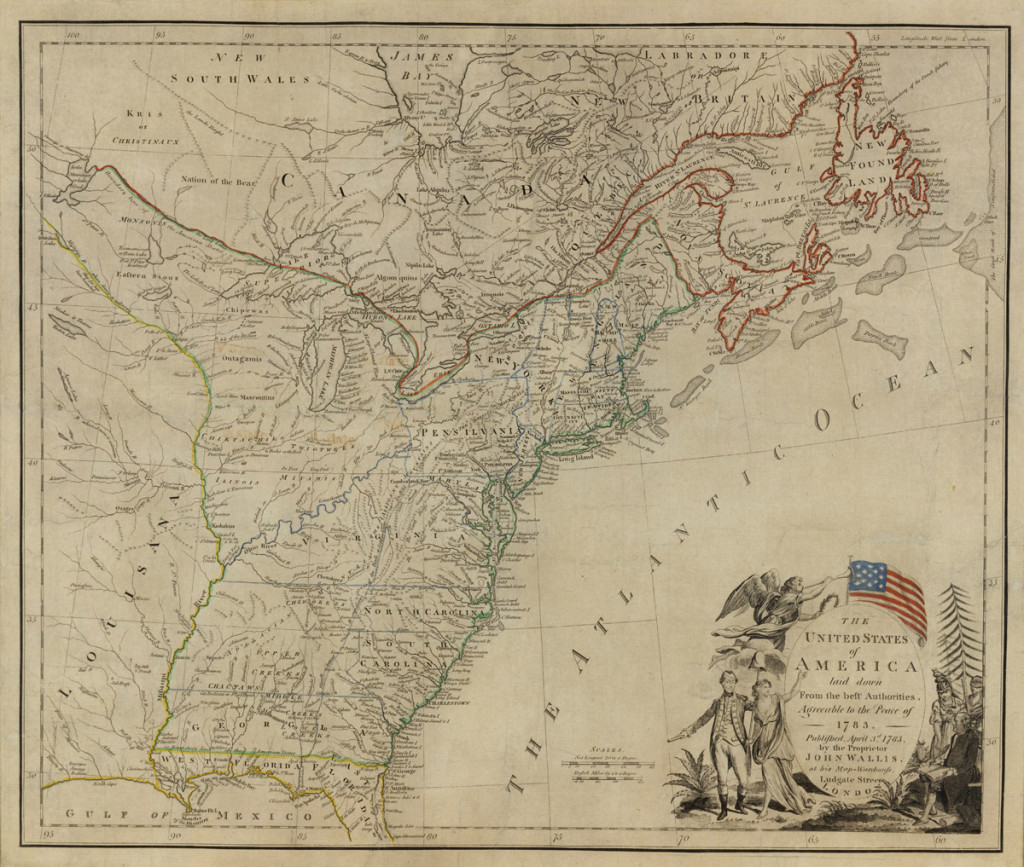

The United States of America Laid Down From the Best Authorities, Agreeable to the Peace of 1783

Published by John Wallis

London, England; 1783

Etching with burin work and watercolor on laid paper

1968.517a,b Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont

The 1783 map by John Wallis, The United States of America, was one of the first published in Europe to recognize the new nation’s independence. It connected with American citizens on three levels—offering visual proof that the nation was real; linking the nation’s outline to the symbol of the American flag; and introducing two national heroes into the iconography of eighteenth-century cartouches. Using the likenesses of George Washington (paired with the figure of Liberty) and Benjamin Franklin (paired with Wisdom and Justice), the Wallis cartouche quickly became a model for innovative transfer printings. Everyday objects such as milk jugs and scarves presented a combination of the nation’s map and the Wallis cartouche in celebration of American independence.

Plate, Bowl, and Jug

(Plate and bowl) Probably Herculaneum factory

Liverpool, England; 1790–1815

Lead-glazed earthenware

1971.0189 Gift of Mr. and Mrs. John Mayer, 2007.31.10 Gift of S. Robert Teitelman, 1958.1193 Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont

Handkerchief

Henry Gardiner

Wandsworth, England; 1792

Engraving on cotton

1959.957 Gift of Henry Francis du Pont

Liberty Displaying the Arts and Sciences

Samuel Jennings

London, England; 1792

Oil on canvas

1958.120.2 Museum purchase with funds provided by Henry Francis du Pont

“Americans, unshackle your minds and act like independent beings!” were exhortations common during the first decades after independence. In response, citizens took up the challenge, demanding more, better, and, above all, equal education. Allegorical paintings such as Liberty Displaying the Arts and Sciences captured the public’s sentiment. Surrounded by symbols representing the arts and sciences, the figure of Liberty hails the new nation’s commitment to providing education for all, including African Americans. A set of broken chains at her feet not only comments on the recent liberation from England but promotes the liberation of American slaves. A wall map and globe showing the nation’s outline illustrate the importance of maps for underscoring the symbolic message of liberty.

Every child in America should be acquainted with his own country . . . The people in this country, even the higher classes, have no correct knowledge of the United States. Such ignorance is not only disgraceful but is materially prejudicial to our political friendship and federal operations.

Noah Webster, On the Education of Youth (1788)

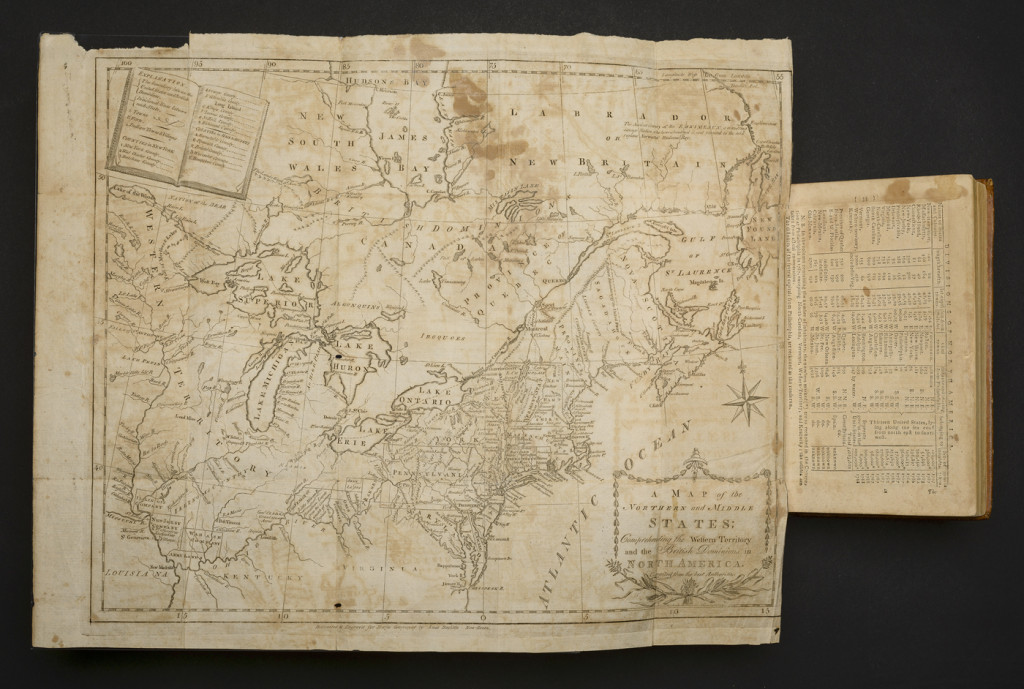

The American Geography

Jedidiah Morse

Elizabeth Town, New Jersey: Shepard Kollock, 1789

E164 M88 Printed Book and Periodical Collection, Winterthur Library

Often called the father of American geography, Jedidiah Morse was a New England minister who transformed geography books and maps into a best-selling genre. Using write-in questionnaires to update information about states and towns, Morse developed a textbook series that easily adapted to the changing American landscape. His American Geography was the nation’s first encyclopedic book on geography, and it revolutionized the study of the subject itself. Previous generations studied Europe first and America last. By placing the American map and chapters about the continent at the beginning of his books, Morse turned the academic world upside down by centering attention on the first modern republic.

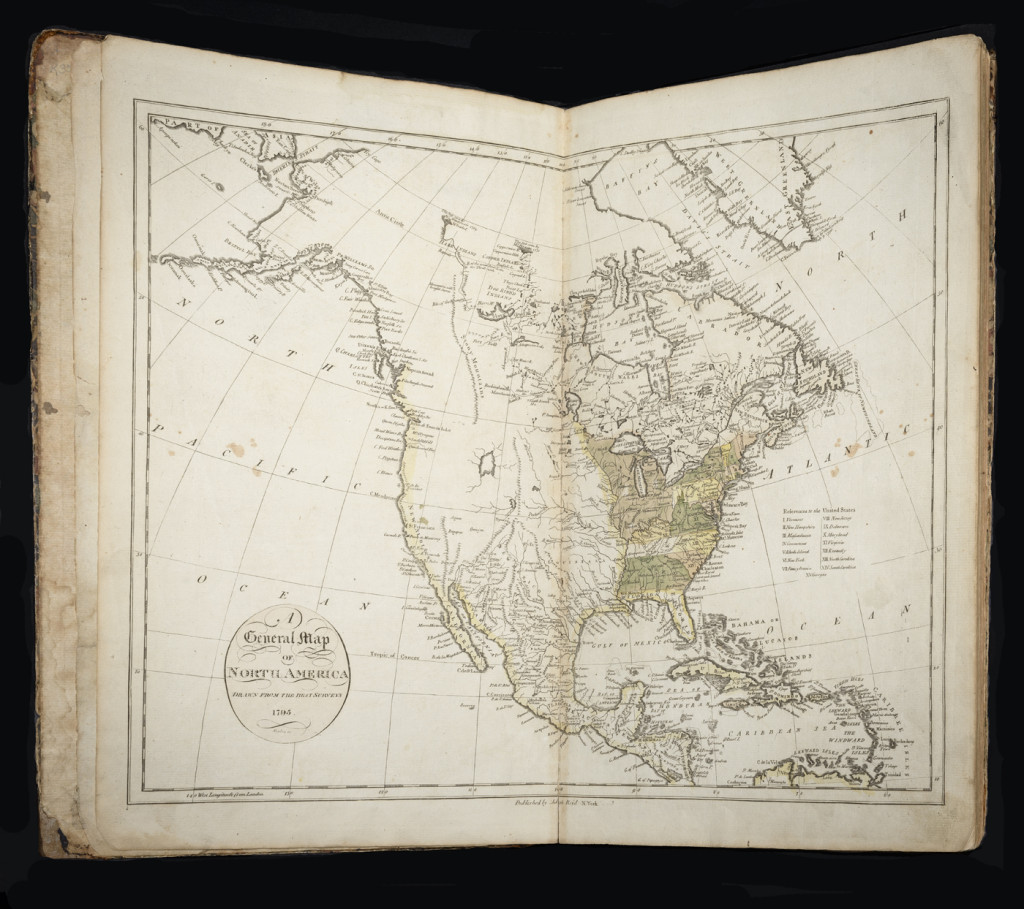

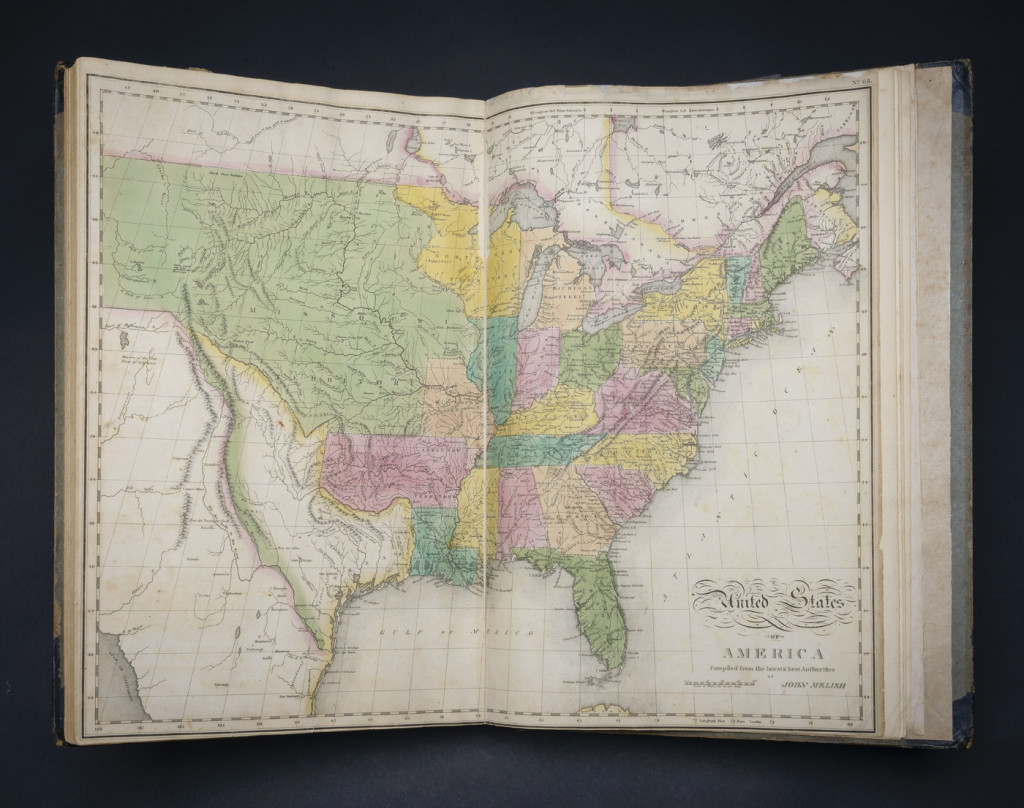

The American Atlas

John Reid

New York, New York: John Reid, 1796

G3702 R35 F Printed Book and Periodical Collection, Winterthur Library

A spate of new atlases made in the United States greatly popularized the cartographic image of the nation. For publishers such as John Reid, the national map worked like a table of contents at the beginning of the atlas, prefacing the maps showing the states. Always the largest map in the book, it reflected the new political model of checks and balances. Although the map’s size allowed for the nation’s greater territory to encompass the relatively smaller states, it balanced the new federal principle of unity with that of state autonomy.

A Complete Genealogical, Historical, Chronological, and Geographical Atlas

C. V. Lavoisne

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: M. Carey & Sons, 1821

G1030 L41 F Printed Book and Periodical Collection, Winterthur Library

Map circulation in America increased to unprecedented numbers with the 1817 invention of machine-made paper by Delaware brothers Joshua and Thomas Gilpin. One of the first books to use their paper was the folio atlas by C. V. Lavoisne. Advertised for the “Price of Thirty Dollars, Half Bound” (a whopping $547 today), the paper in the atlas was noted for its fine uniformity of texture and freshness of color. Within a decade, paper machines generating sheets that were 1,000 feet long and 27 inches wide superseded hand-manufactured paper. Although the application of color was done by hand until the 1860s, machine-made paper made maps and atlases affordable to every man and woman.

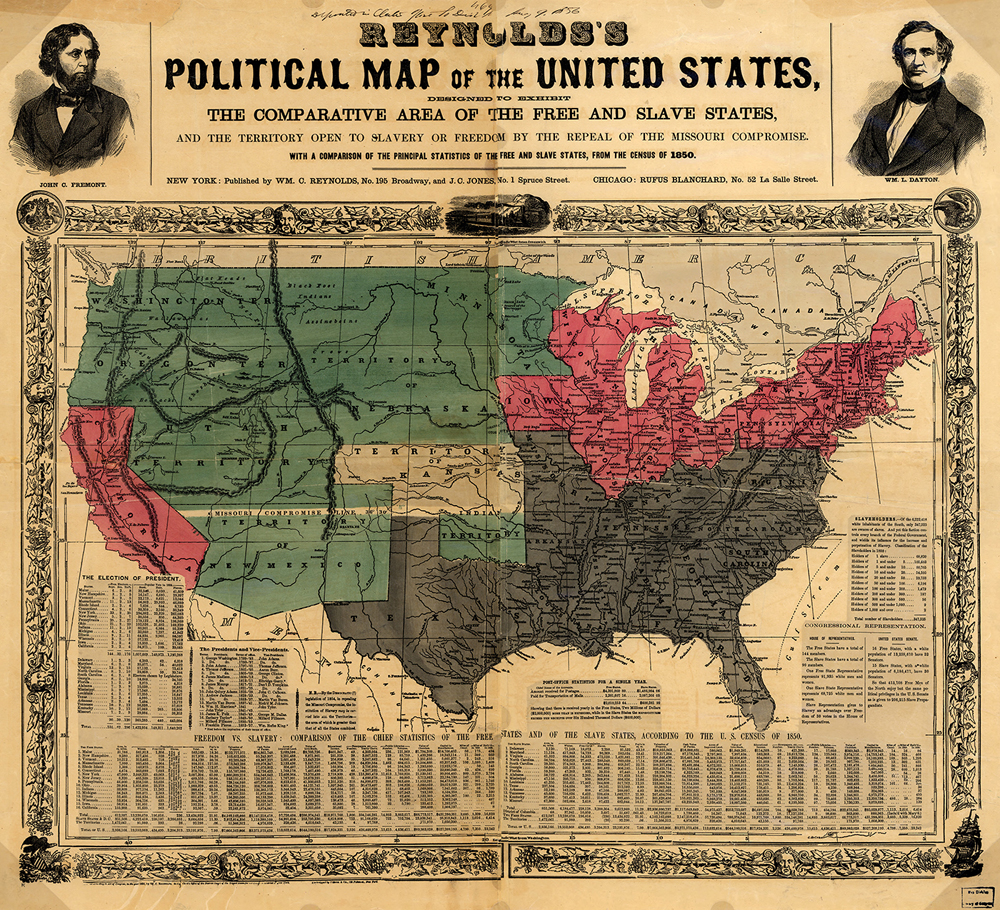

Reynolds’s Political Map of the United States, Designed to Exhibit the Comparative Area of the Free and Slave States and the Territory Open to Slavery or Freedom by the Repeal of the Missouri Compromise

(exhibited as photographic reproduction)

William C. Reynolds and J. C. Jones

New York, New York; 1856

Hand-colored lithograph

Library of Congress

Before the widespread use of photographic reproduction in the late 1800s, maps were either hand drawn or printed using the intaglio process (etching, engraving, woodcut) or planographic process (anastatic, lithographic, or offset). Once drawn or printed, mapmakers and consumers could choose to add color if they so desired. Colors made maps attractive but mostly served to emphasize boundaries or coded information, such as the designation of slave and free states before the Civil War.

Gilpin’s Mills on the Brandywine Creek

Enoch Wood & Sons

Burslem, England; 1820–46

Lead-glazed earthenware

1958.1364 Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont

Thomas Gilpin was the first to successfully produce machine-made paper in America at his mill on the Brandywine Creek, outside Wilmington. Earlier papermakers depended on labor-intensive manual work to create single sheets of paper from rags and other textile materials (usually cotton and linen). The mechanized process allowed for the creation of “endless” paper rolls that were up to sixty inches wide. With the adoption of inexpensive wood pulp after the 1840s, the combination of machine-made paper and steam-powered printing presses was responsible for the dramatic increase in the output and range of printed materials available to the American public.

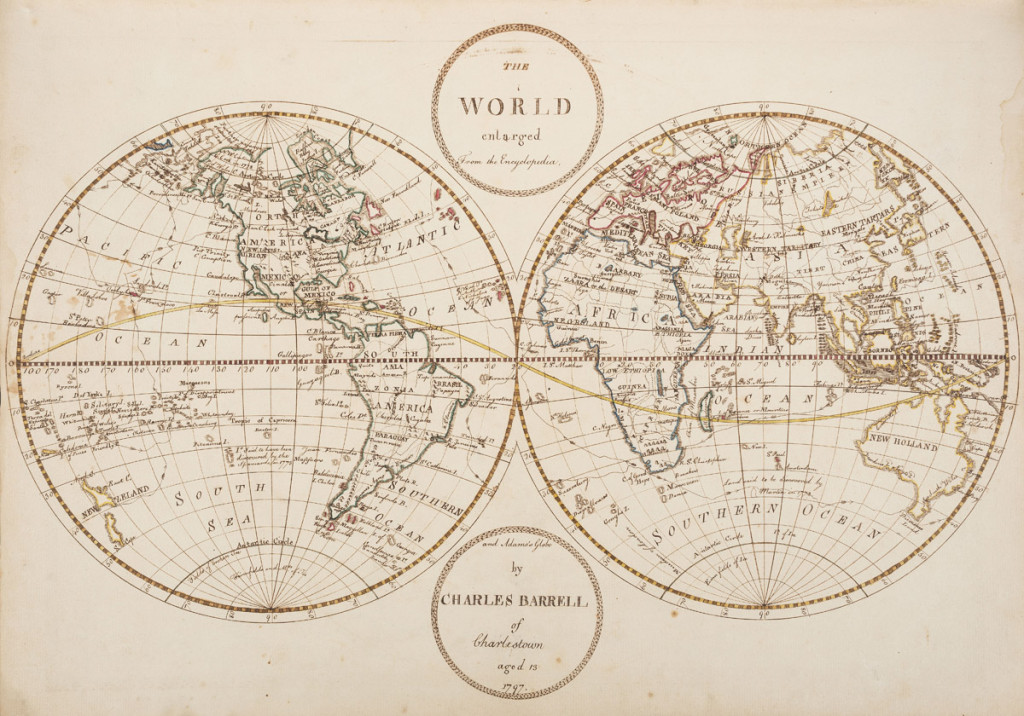

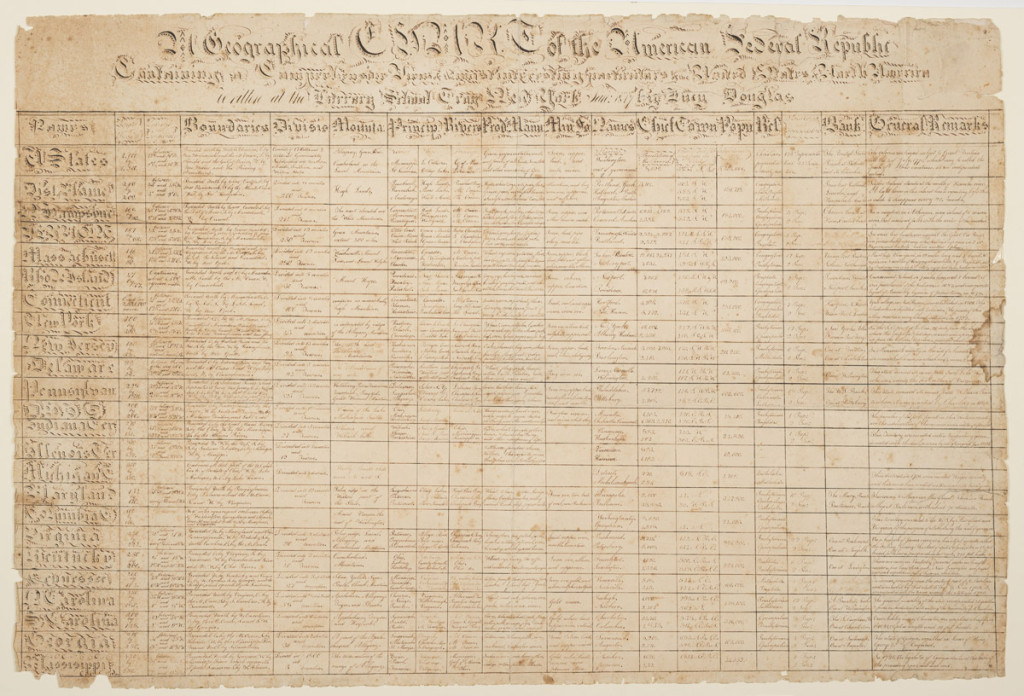

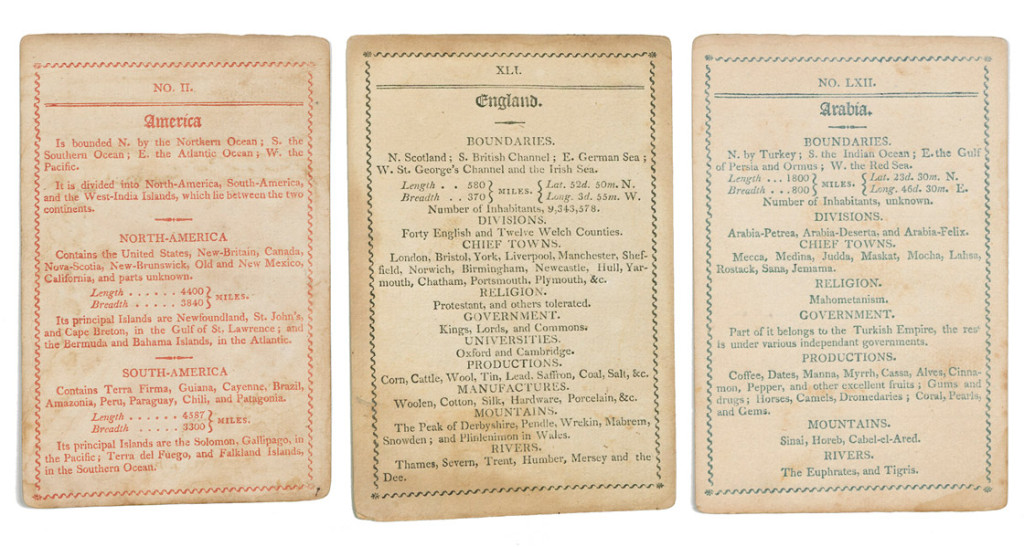

Along with the new emphasis on map studies came the question of how best to test map knowledge. Public schools as well as private academies singled out map learning through public examinations, school fairs, and student projects that applied map knowledge to a range of educational goals. Hand-drawn maps tracked the tale of Captain Cook’s famous voyage to the Pacific. Handwritten statistical tables tallied the geography of states and the nation, and map samplers were worked by young girls everywhere. Overall, student projects engaged a broad spectrum of materials and skill sets, including drawing, penmanship, memorization, and needlework.

The Miscellaneous Works of Charles Barrell(with detail)

Charles Barrell

Boston or Medford, Massachusetts; 1797

Fol. 256 Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, Winterthur Library

A Geographical Chart of the American Federal Republic

Lucy Douglas

Troy, New York; 1817

Ink on paper

Col. 730 Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, Winterthur Library

Needlework picture

Worked by Mary Franklin

Pleasant Valley, New York; 1808

Silk embroidery with watercolor and ink on silk

1957.552a,b Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont

Geographical study cards

David Allinson

Burlington, New Jersey; 1805–6

Ink on laid paper

1963.87.1-.70 Museum purchase

Wisdom Instructing Youth in the Science of Geography

United States; about 1800

Silk embroidery and paint on silk ground

2013.2.1 Museum purchase with funds provided by the Henry Francis du Pont Collectors Circle

This rare silk embroidery celebrates the centrality of maps in the education of young Americans. In a playful allegory of map learning, the imaginary figure of Wisdom offers guidance to a study group working on a large unframed map. Pointing to the map with one hand and with a spear to the architectural space of a classical temple, Wisdom enjoins the students to look at the map as a window to higher learning and the world. The design links classical ideals with Enlightenment practice. The colors of the silk show nature and culture in soft earthen hues. The whiteness of the hand-painted map elevated by a modern reading stand not only illuminates the students but becomes a beacon of modern education.