Maps in a Woman’s World

Contrary to popular notions today, American women were deeply invested in maps, mapmaking, and map displays. Female academies and mothers who home-schooled their children held competitions in map drawing and map reading. Needlework samplers and embroidered maps were staples of interior decoration in parlors, studies, and bedrooms. In public, fashion-minded women used map fans or handkerchiefs as accessories when celebrating military victories or national holidays. Decorative artists frequently transferred map motifs—especially those showing individual states of the Union—to textiles and ceramic wares, thus enabling their female users to participate in the nation’s civic affairs.

Mother Holding Thomas Carew Hunt Martin as Infant, June 22, 1857

(exhibited as photographic reproduction)

Watercolor on paper

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Most significantly, maps offered middle- and working-class women the chance for mobility. A burgeoning map industry enabled women to work from home as map painters and atlas binders. Maps also provided the kind of “useful entertainment” through which women and children could not only bond at home but also treat themselves to rare moments of carefree “travel.” As diaries, ladies’ magazines, and sentimental novels repeatedly tell us, with the aid of maps, women turned into “armchair geographers” who could visit distant relatives or exotic places without physical constraint or moral prejudice.

The Bowie Children

Dominic W. Boudet

Maryland; 1812–15

Oil and gesso on canvas

1999.19.3 Gift of Katherine Gahagan, Michael H. du Pont, and Christopher T. du Pont in memory of A. Felix du Pont, Jr.

The six children of Colonel Washington and Margaret Bowie of Prince Georges County, Maryland, are shown standing in a room around a green baize-covered table that holds a globe, book, and map (left to right): Robert (age 5), Thomas (age 13), Washington (age 8), Margaret (age 10), Richard (age 6), and Mary (age 10). Compositions like this signified the family’s commitment to geographical education while also affirming the children’s social status and civic virtue. By juxtaposing the tools of geography with the open window, the painting connects the children to the world at large. By showing North America and the area of the United States on the globe, the portrait acknowledges the family’s commitment to the nation and its new democratic values.

This morning I was introduced to my new brother, & am much pleased with him, did not attend school, sewed, & attended to domestic affairs. Tuesday The forenoon I spent in sewing at home, In the afternoon went to school, drew on my map of Connecticut & read in the inquisitor, which is a very humorous thing. Wednesday. Came to school & read geography to Miss Chittenden, In the afternoon recited my part & wrote.

Diary of Lucy Sheldon, February 1802. Age 13

Needle skills were an important part of a girl’s education, whether she was taught at home by her mother or at a young woman’s academy. When eighteenth-century pedagogues introduced the study of geography to improve exercises in memorization, basic instruction in map reading was combined with manual training in needlework. Between the 1770s and 1840s, embroidered maps, map samplers, and even globes were popular assignments for celebrating a girl’s academic accomplishments.

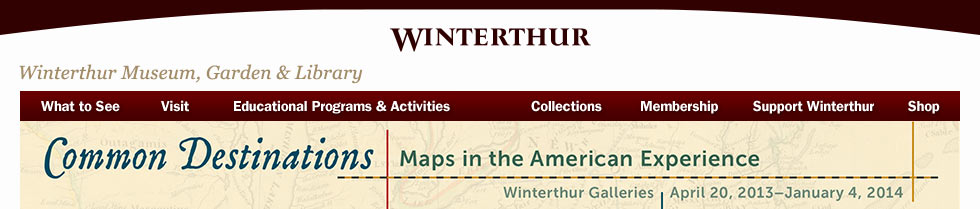

Plan of the City of Washington

Worked by Elizabeth Graham

Alexandria, Virginia; 1800–1803

Silk embroidery on linen

2008.57 Gift of Ruth McLaine and Family

When she was 13 years old, Elizabeth Graham embroidered a copy of The Plan of the City of Washington, originally designed by Pierre L’Enfant in 1791 and engraved by James Thackara and John Vallance in 1792. Her sampler gives testament to the varied nature of map reproduction. By embellishing her map with embroidered and painted oval cartouches showing George Washington and the figures of Justice, Hope, and Liberty, young Elizabeth combined patriotic themes with the decorative arts. The addition of sprays of flowers and vines to each cartouche gives further testament to her extraordinary needlework skills and patience.

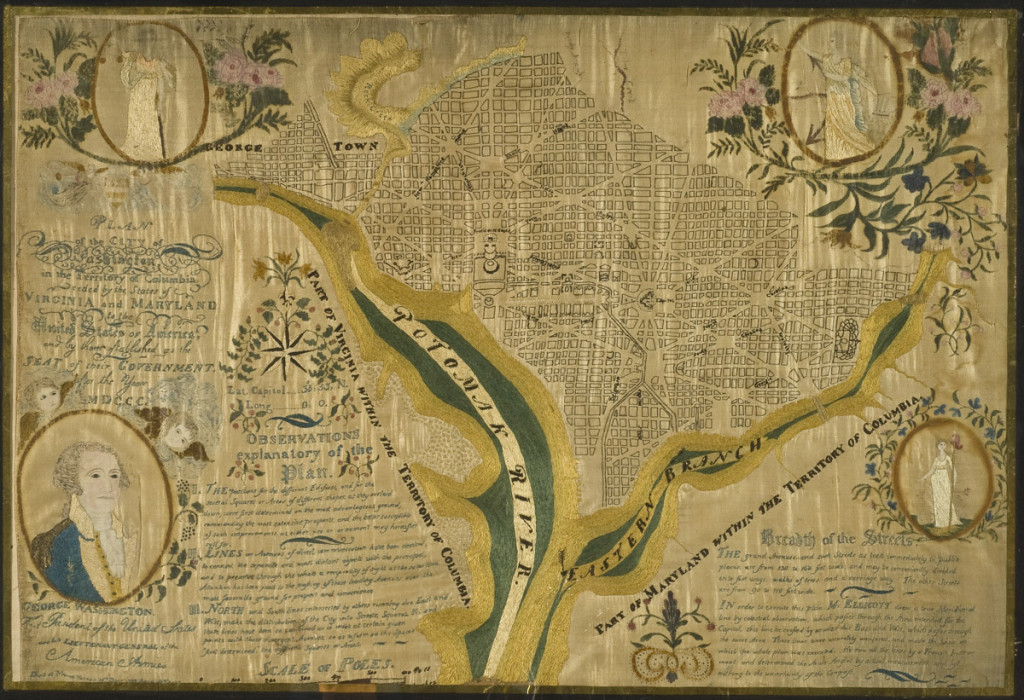

Globe sampler

Worked by Ruth Wright

Westtown, Pennsylvania; about 1815

Ink and silk embroidery on silk and wood

1969.46 Museum purchase

In the early 1800s, sewing and needlework were an important part of the curriculum at the Westtown School, established by the Quakers near West Chester, Pennsylvania. The school is particularly well known for its students’ preparation of textile globes. Using scraps from sewing classes, young girls like Ruth Wright turned the tedious study of geography into a creative object lesson. On her globe sampler, the continents, countries, and oceans are marked in ink; the equator and arctic circles are noted with white silk; the Tropic of Capricorn and Tropic of Cancer are worked in red silk. The thicker threads of the longitudinal lines stand out in relief against the background material of faded blue silk. Textile globes not only highlight the transfer of two-dimensional features to three-dimensional displays but also document the tactile nature of map lessons.

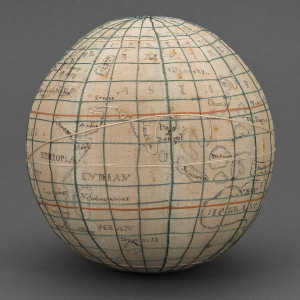

Map sampler

Worked by Elizabeth Loeser (or Leoser)

Penn Township, Pennsylvania; about 1831

Silk, cotton, and wool embroidery on linen

1994.33 Anonymous gift

The curriculum in public schools that provided education for working-class and middle-class girls included the assignment of map samplers in order to instruct pupils in needle skills and test their knowledge of geography. This sampler by Elizabeth Leoser uses the cross-stitch, back stitch, and seed stitch to mark the boundaries of the state and counties as well as rivers and mountain ranges.

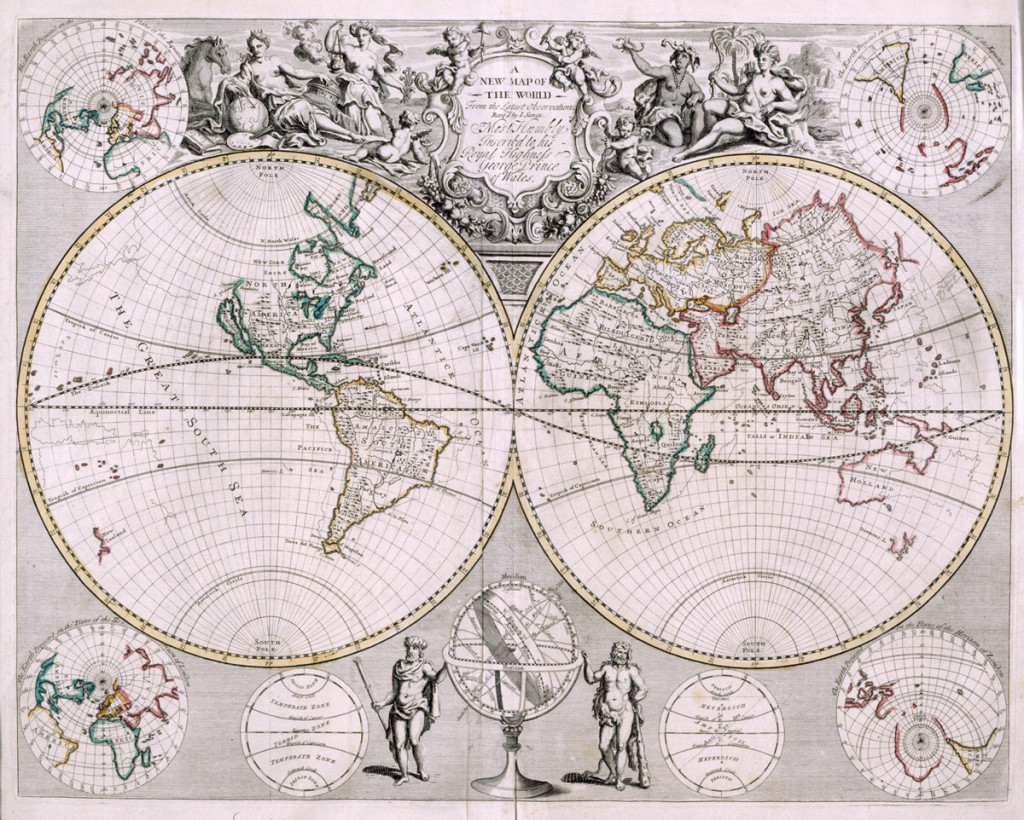

A New Map of the World from the Latest Observations

Engraved by John Senex

Published by Daniel Browne

London, England; 1721–40

Line engraving with watercolor on laid paper

1964.510 Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont

World maps, in particular political maps showing nations and their colonies, were a fixture in early American homes. They enabled women to participate, although from a distance, in political and scientific affairs. Like all maps, world maps were never neutral. For John Senex, they provided a media platform for advertising his craft and skill. For the map owner, intricate border designs and allegorical figures transformed the object into a spectacular wall ornament, telling an early story of globalization. On the top panel seen here, four female figures represent the continents (left to right): Europe, Asia, Africa, and America. The two cherubs that frame the cartouche signal the map’s British origins: “British liberties” (cap on staff) and “the rule of law” (scroll).

Four Continents (Handkerchief)

England; 1815–30

Cotton

1964.1484 Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont

Beginning in the mid-1700s, it was the norm for map engravers, book illustrators, and political satirists to use female figures to represent the four continents. The figures were usually displayed with accessories deemed appropriate for the context. For example, the figure of Europe on this handkerchief is presented with objects representing the arts and sciences; the figure of America symbolizes the new nation and its democratic ideals with a liberty cap, staff, and shield bearing the nation’s insignia. Such allegorical images also reflected a cultural bias. They fostered subtle narratives about European superiority over non-European cultures, especially Native American and African cultures.

Little W. has had books and gifts enough—a large cow and milkmaid from the Miss Nortons and a volume of Mrs. Barbauld’s Lessons, in which he reads as well as I can, and a beautiful little dissected map, all of which have made him supremely happy . . . It is really curious to hear him going over all the names of places, States, lakes, rivers, etc., on his map—it pleases him exceedingly and he is as regular as clock work in all his operations.

Diary of Anne M. Cary, January 1828

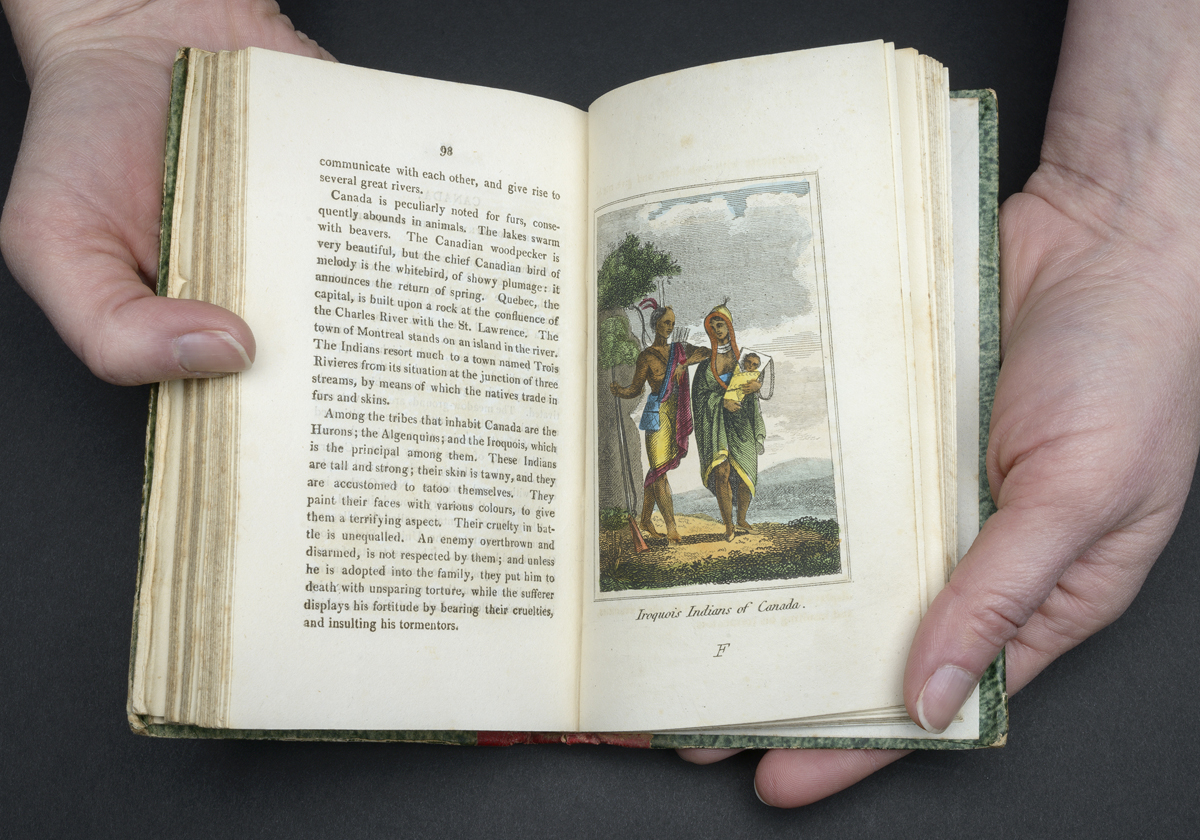

A Geographical Present: Being Descriptions of the Principal Countries of the World; with Representations of the Various Inhabitants in their Respective Costumes

Mary Anne Venning

London, England: Darton, Harvey, and Darton, 1817

G125 V46 S Printed Book and Periodical Collection, Winterthur Library

Pocket books, ranging from geographical primers to novels, offered companionship for women during their leisure hours. They were also favorite reading materials consulted during map lessons and geographical games. Using illustrations borrowed from ornamental maps, geographical descriptions further reinforced stereotypical views of people and their customs.

Pocket

Pocket

England; 1775–1800

Cotton and linen

1960.195 Museum purchase

Built-in pockets for women are a relatively modern invention. From the mid-1600s to the mid-1800s, women often wore one or two pockets tied under the top layers of their clothing. Slits cut in the garments covering the pockets provided access to the goods within, which often included personal items such as money, tools for needlework, or small books and papers. Constructed from plain and printed fabrics to suit the wearer’s tastes, pockets were often embellished with elaborate embroidery or appliqué work.

Tight Lacing; or, Fashion before Ease

(exhibited as photographic reproduction)

Published by Bowles and Carver

London; about 1770

Black and white mezzotint engraving with period hand color

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Museum purchase

L’Amérique (Fan)

Jean Lattré

Paris, France; 1779–80

Engraving with watercolor on paper, pasteboard, wood, brass

1965.2116 Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont

As rare as it is unique, this adaptation of a map into a fashionable fan is only one example of the vast crossover appeal maps had in the 1700s and 1800s. True connoisseurs could find maps transferred to parlor screens, window shades, porcelain figurines, ceramics and earthenware, gloves, and neckties. Often serving no immediate cartographic purpose, such objects are today called “cartifacts.”

Map

Jane Naomi Strong

Hartford, Connecticut; 1827

Ink and watercolor on paper

2013.2.2 Museum purchase with funds provided by the Henry Francis du Pont Collectors Circle

“Mappery,” or the art of planning and designing maps, was a fashionable subject advertised by private schools seeking to attract female students during the 1820s and 1830s. Starting with a blank sheet of paper, students drafted their maps from scratch. Instead of making copies of existing maps, they constructed grid lines and topographical contours using the same manuals that informed army officers and land surveyors. Similar to professional mapmakers, schoolgirls like Jane Naomi Strong applied the principles of selection and generalization. Once finished, the map drawings frequently won recognition at fairs and exhibitions.

A Female Philosopher in Extasy at Solving a Problem

(exhibited as photographic reproduction)

London, England; about 1770

Mezzotint and engraving with watercolor on laid paper

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Satirical prints, usually made by men, lampooned the popularity of maps and globes among women. Because women had little access to professions such as surveying or architecture, exercises in geometry were made more meaningful for them through maps and cartographic assignments. Women’s diaries, educational treatises, and novels document that solving map-reading problems at school or during parlor games was standard fare for young women. This slightly risqué print, A Female Philosopher, pokes fun at map reading while revealing a persistent bias against educated women. It questions the motives of women who are working with maps in private. Do maps give the pleasure of knowledge or the knowledge of pleasure?